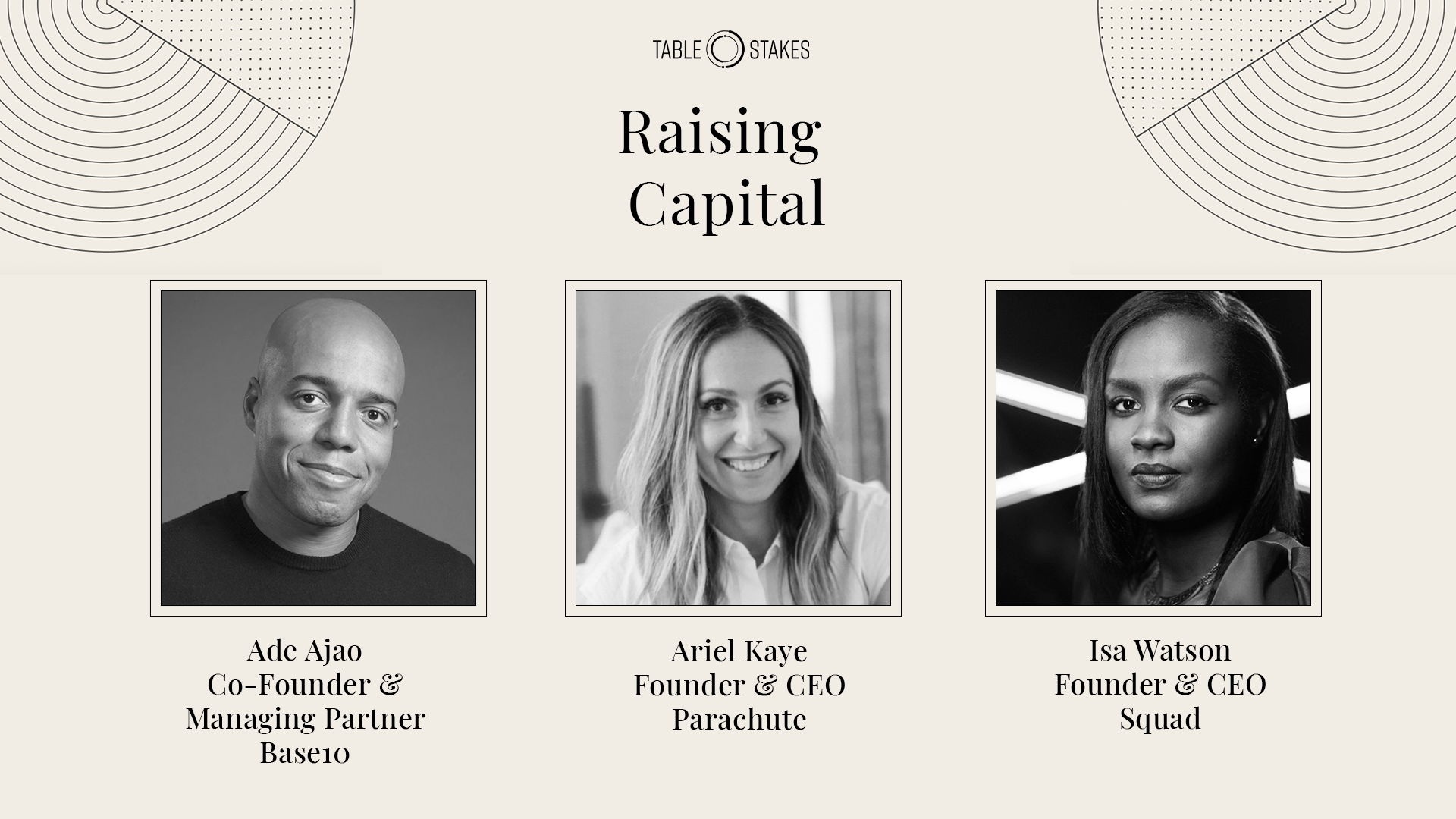

Raising funds is an exciting, stressful, and entirely unique part of every founder’s journey. In our Raising Capital panel at the 2020 Table Stakes Summit, we joined Ade Ajao (co-founder & managing partner, Base10), Isa Watson (founder & CEO, Squad), and Ariel Kaye (founder & CEO, Parachute) for an honest discussion about their fundraising experiences.

(This transcript has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.)

Hearing “no” from investors

Ade: Isa and Arielle, thank you both so much for being here. Let’s go straight into it: I think when you Google “How to raise capital for a startup,” one of the first things you’ll see is that you have to be ready to receive a lot of “no’s.” What are some investor “no’s” that have particularly stuck with you?

Isa: I think founders have a tendency to take the word “no” too personally, because it’s like, “This is my baby. I’ve put everything into this, I think about this 24/7.”

But the interesting thing, at least in my experience, is that the firm that led our last round – a pretty notable firm – actually told us “no” at first. They said “no” in January, and by April, I had a term sheet. So sometimes, “no” can also mean “I want to see more,” or “I want to take another look at this later.” Sometimes no does mean no, but a “no” can also be translated into a “yes” as well. That’s something that has always stuck with me.

Ariel: I think there are a few different kinds of “no’s,” right? Some very painful types, in my experience. There’s the type of “no” where you quickly realize that your time’s been wasted — perhaps the investor is just looking to learn more about your business, or your category, or the team you’re building. That kind of “no” is frustrating because your time is precious, and you want to be respected for your time.

“When you feel passionate about what you’re building, and when you’re certain that what you’re doing adds value and you believe in it…it’s important to let those “no’s” just be a reminder that they don’t get it.”

There’s another type of “no” that’s probably even more painful, which is the “no” that comes after countless meetings, or a partner presentation — you know, the ones that you think are really at the finish line. That “no” can make you feel a bit more blindsided.

But when you feel passionate about what you’re building, and when you’re certain that what you’re doing adds value and you believe in it…it’s important to let those “no’s” just be a reminder that they don’t get it. I’ve had investors come back to me years later and say, “You’re the one that got away,” and “I wish I would have invested sooner.” And that can be validating. [Fundraising is] just a process, and you have to be resilient. You have to have thick skin.

Ade: If it makes anyone feel any better, when I think back to my time as an entrepreneur, I think the worst “no” I got when I asked an investor what he didn’t like about the business, he said “It wasn’t really the business. It was the founder. So if that ever changes, let me know.” We did not talk much after that (laughs).

Venture capital vs. other types of funding

Ade: Isa, going back to you — why did you decide to go straight to venture capital? Did you ever consider any other kind of funding?

Isa: I think venture capital is prominent because it gets a lot of coverage, right? That’s how you can land a Tech Crunch piece, or a top Wall Street Journal piece, et cetera. But oftentimes, we don’t think about the fact that there’s so many different forms of capital. You have to decide which one is best for your business.

For a venture-backed business, you’re going to want to talk about a total addressable market that’s in the billions. You’re going to want to talk about being able to get a significant piece of that market — and if you can achieve that by leveraging a certain type of efficient process, then that’s a VC-backable business.

“Venture capital is just one form of fundraising. If you’re not a fit for VC, I don’t think that’s a bad thing.”

Oftentimes I find myself giving advice to founders with service businesses, or brand agencies, that maybe venture capital isn’t the right path for you. Your path is going to be a more steady, consistent pathway. Venture capital is just one form of fundraising. If you’re not a fit for VC, I don’t think that’s a bad thing. You’ll probably get less diluted (laughs).

Ariel: When I started in 2013, venture capital was all I really knew. I wasn’t aware of other alternative forms of raising. So I joined an accelerator program, and through that was introduced to a number of VCs. That was just what I thought the path was — but venture is not the only way to raise capital. There are alternative forms of capital. At this point we’ve raised money from angel investors, family offices, private equity funds…I don’t think there’s a cookie-cutter way to raise money.

At the end of the day, when meeting investors, you want to make sure that you have a similar vision and similar expectations. You want to know how you’re going to spend that capital and what their appetite is for potential outcomes — is it a five-year plan? A ten-year plan? What are the time horizons they’re thinking about? Different types of funds have different types of mandates that they’re working with.

“At the end of the day, when meeting investors, you want to make sure that you have a similar vision and similar expectations.”

Ade: I think you touched on many good points. As a former founder, I’ve found it interesting to experience firsthand the incentives and motivations you have as a VC. I wish I had understood that better when I was choosing who I was going to partner with.

Choosing investors carefully

Ade: Isa, you have really solid venture capital backers. How did you choose those particular partners?

Isa: There are a few elements — one is more rational, and another is more relationship-oriented. For the rational standpoint…we had a lot of top-tier firms that wanted to participate in our seed round, but I didn’t want to take on that signaling risk. For instance, if you have Sequoia on your cap table too early, and then you get to the Series A and Sequoia doesn’t lead it, then Lightspeed’s looking at you crazy talking about, “Oh, well why isn’t Sequoia leading it? Maybe we don’t want to go too close to that.” So as a founder, I’m really interested in the stage that they specialize in.

“When it comes to selecting people for your cap table…who’s going to have those hard conversations with you, and really look out for your best interests?”

The second thing – I find that people don’t like to talk about this often, but I’m just going to keep it a hundred percent real – is that as a VC-backed CEO and founder, somebody’s going to try to fire you. So when it comes to selecting people for your cap table, who will actually pull you into a corner and be like, “This is what’s happening.” Who’s going to have those hard conversations with you, and really look out for your best interests?

Those things matter to me a lot. Do I like you? Do I trust you? I do a lot of founder back-channeling. I want to know all the dirt. Give me all the tea so I can make the best decision for me. When you talk to founders, a lot of times they think VCs have the power because they have the money. No, no, no. They need us to make the money. They need us more than we need them. I think it’s an honor for VCs to be invested in us. It’s a privilege. We should treat it as such, and make sure we’re bringing on the best strategic partners.

Ade: Do you feel that when you’re transparent with a VC, they respond in kind?

Isa: The VC world is a very insular world. When I first came into the VC world, I felt intimidated. But the reality is that they’re human, I’m human. We both have 46 chromosomes. There’s no reason for me to be intimidated by them. So for me, I show up as me. My board loves it…but I’m not trying to be for everybody. People should understand that with VCs, you’re not going to just marry anybody. You shouldn’t just jump into bed contractually with anybody that you’ll be working with for ten years.

“When I first came into the VC world, I felt intimidated. But the reality is that they’re human, I’m human. We both have 46 chromosomes. There’s no reason for me to be intimidated by them. So for me, I show up as me.”

Ariel: One of the benefits of working with investors who are former operators is that they’ve been in your shoes. There’s something to be said about having someone that you can look at and say, “I need you to take off your investor hat. Now put on your founder hat, or put on your operator hat, and let’s talk through how to tactically fix this problem.” That’s just an added benefit, and something to think about as you’re kind of thinking about who you want to be involved in the company.

Ade: Obviously as a former operator I have a little bit of bias here…but do you find that there is a level of empathy, founder-to-founder, that’s more difficult to achieve with purely financial-background LPs?

Ariel: Yes and no. I think it’s on a case by case basis. I have some really phenomenal investors who are purely professional investors, and I have really great relationships with them. But yeah, I think in some cases it can be easier to be a little bit more vulnerable, and to see that empathy and perspective, with a founder. There’s something different about the experience of being a founder — the pressure, the weight, the intensity. So I do think yes, there is a bit of a difference, but I think there are some exceptions to the rule.

“The thing about being a founder is that we’re always feeling like we can do better.”

Isa: The thing about being a founder is that we’re always feeling like we can do better. I find that there’s a delineation between how I talk to, and lean on, my “former operator” investors. There’s just a level of empathy and honesty that I can have with them. Quite frankly I would say that ever since I became a founder, pretty much all my new friends are founders. It’s a really weird experience that only a handful of people know and understand.

Fundraising expectations vs. reality

Ade: When you were thinking about fundraising, how did you decide how much to raise, what valuation, and what was going to be the use of funds? How much did your plan end up mirroring what finally happened?

Ariel: I’ve raised quite a few rounds at this point (earlier rounds). In terms of hindsight, I probably under-raised, which just meant that I had to raise again sooner. But I think there’s a process that we’ve taken on. We think about the use of funds — what are we trying to invest in? What are our strategic initiatives? Is it hiring? Is it technology? Is it marketing? How long do we expect this capital to help us sustain and grow? You want to set those expectations pretty early.

“When you talk to founders, a lot of times they think VCs have the power because they have the money. No, no, no…it’s an honor for VCs to be invested in us. It’s a privilege. We should treat it as such, and make sure we’re bringing on the best strategic partners.”