Venture capital fund managers and their limited partners use several benchmarking metrics to evaluate fund performance.

Assessing a venture capital firm’s performance is more complicated than measuring public asset managers due to limited financial disclosures and the illiquid nature of the private markets.

While the law requires public companies to publish quarterly earnings reports, private companies have no such obligation. Similarly, VCs don’t post financial results on their websites. However, LPs expect updates on the fund’s performance as part of their broader performance discussions.

Each metric used to evaluate performance communicates a different data point; together, the metrics illustrate the fund’s return profile for its outside investors—the limited partners (LP).

The acronyms used to describe fund performance can be overwhelming. For those looking for a crash course, here’s a summary of the primary metrics VCs use to communicate investment performance to investors.

Internal rate of return (IRR)

Internal rate of return (IRR) is a commonly used metric in the VC, private equity, and real estate industries. It measures the annual rate of growth an investment or fund will generate. It’s calculated by setting the current net present value (NPV) of the company’s or fund’s future cash distributions to zero.

The resulting percentage is ultimately determined by the size of the investment, the cash sent back to the LPs, and how long it takes a GP to provide that return. Typically, funds that deploy capital earlier in the fund lifecycle exhibit lower IRRs due to the length of cash outlays versus distributed cash inflows.

Financial professionals use IRR to set “hurdle rates." A hurdle rate is a minimum IRR value a given investment has to meet for investors to deem it successful. In venture capital, LPs typically expect a fund’s net IRR to reach at least 20% by the time a fund has exited all of its investments. Other asset classes, such as public equities, private equity, and real estate have differing IRR expectations.

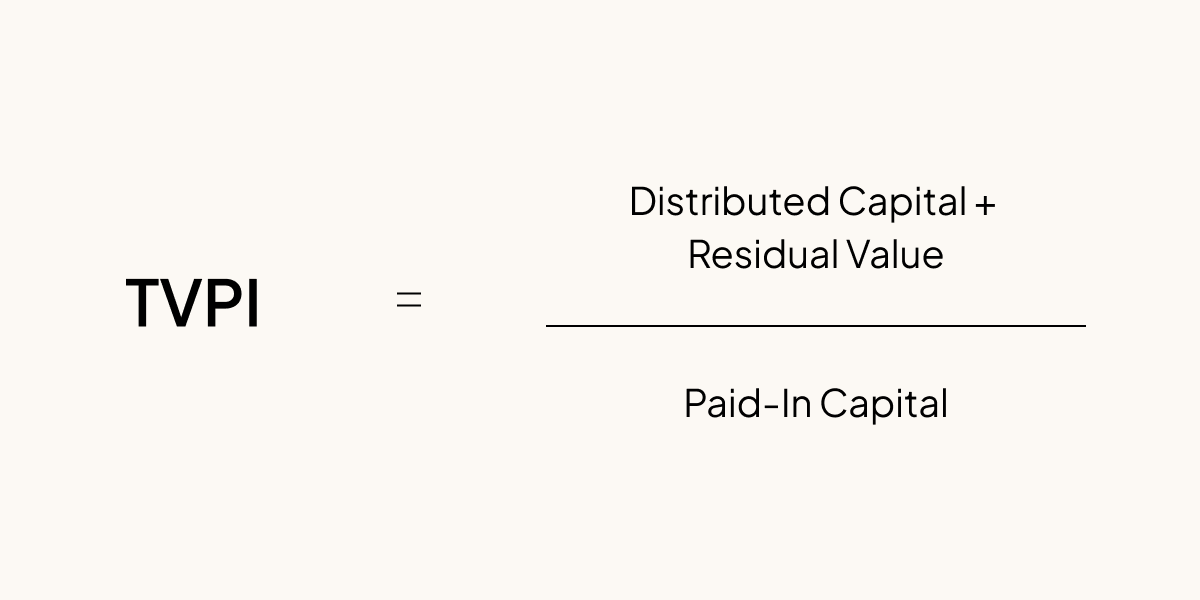

Total value to paid-in (TVPI)

TVPI, or total value to paid-in, is a formula that measures the total value of realized and unrealized investments in a fund in proportion to the total contributions—the paid-in capital. Realized investments represent the capital returned to LPs and unrealized investments have yet to be distributed.

Fund managers and LPs rely on TVPI to determine the total amount of capital a fund could return during its lifecycle at a given point. GPs use TVPI to calculate the total value of a fund before distributions are made, which allows GPs to show investment valuation step-ups to LPs.

TVPI is also the sum of Distributions to Paid-in Capital (DPI) plus Residual Value to Paid in Capital (RVPI). Any multiple above 1.0x signifies that the total value of the realized and unrealized investments in the fund is greater than the amount contributed; any figure below 1.0 means the fund’s value is less than the capital contributed.

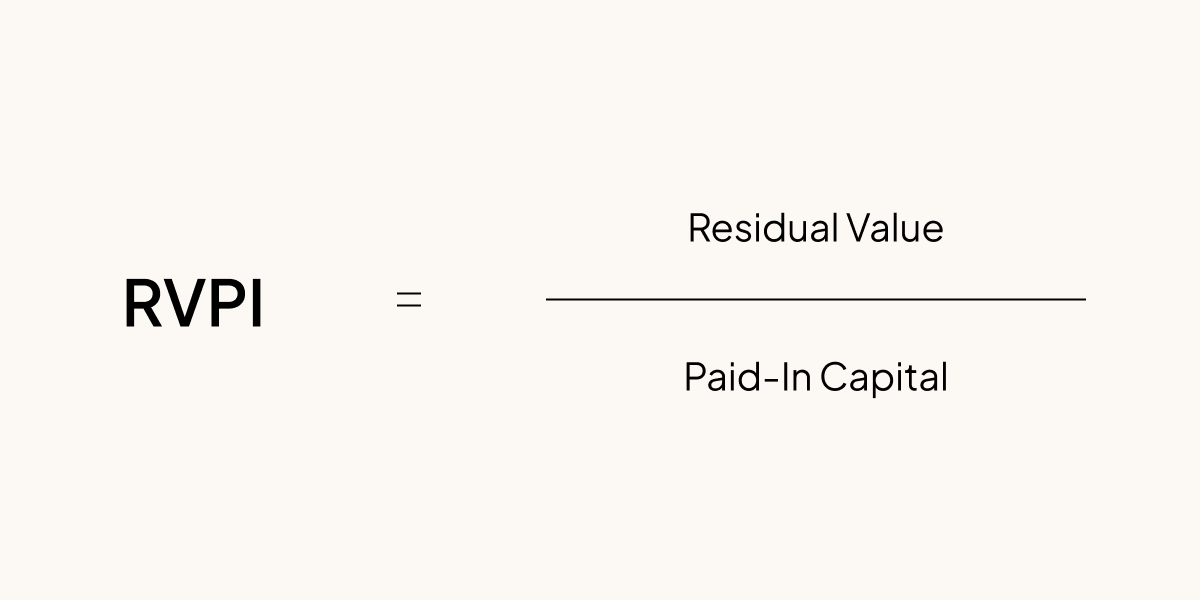

Residual value to paid-in (RVPI)

RVPI, or residual value paid-in, is a formula that measures the residual, or unrealized, value of a fund compared to the paid-in capital. This metric helps LPs determine the fund’s remaining earning potential at any point in its lifecycle. RVPI will be the highest earlier in a fund’s life, after companies have had markups, because investments have not been realized and the fund likely has five-plus years before closing out. In other words, the residual value is at its highest point. This metric offers a glimpse of the fund’s earnings potential, but it’s important to note that it’s not guaranteed.

RVPI will ultimately end up at zero after the general partners cash out of their investments.

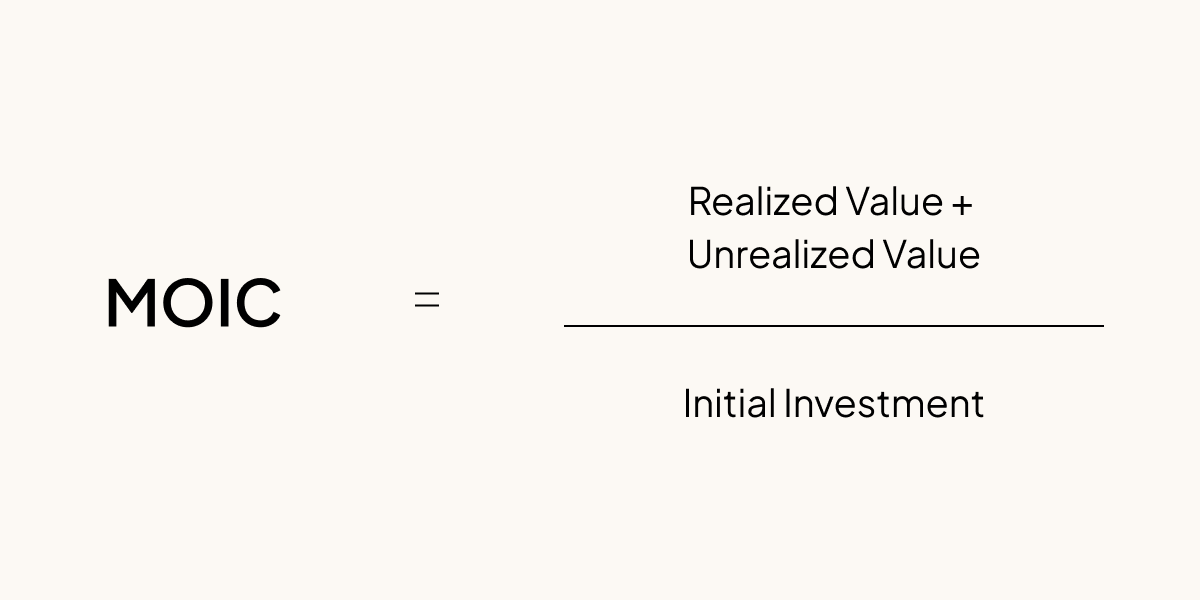

Multiple on invested capital (MOIC)

MOIC, or multiple on invested capital, is a straightforward but important metric that measures the investment multiple on capital paid-in to a fund. It is used across private asset classes and generally used as a gross metric that excludes fees and carried interest; others report net MOIC, which includes fees and carry in the final calculation. Unlike net IRR, MOIC does not change based on how long a fund manager holds the investment. It measures the multiples on the distributions and the book value of the fund—the amount the fund would be worth if it’s sold—compared to the paid-in capital.

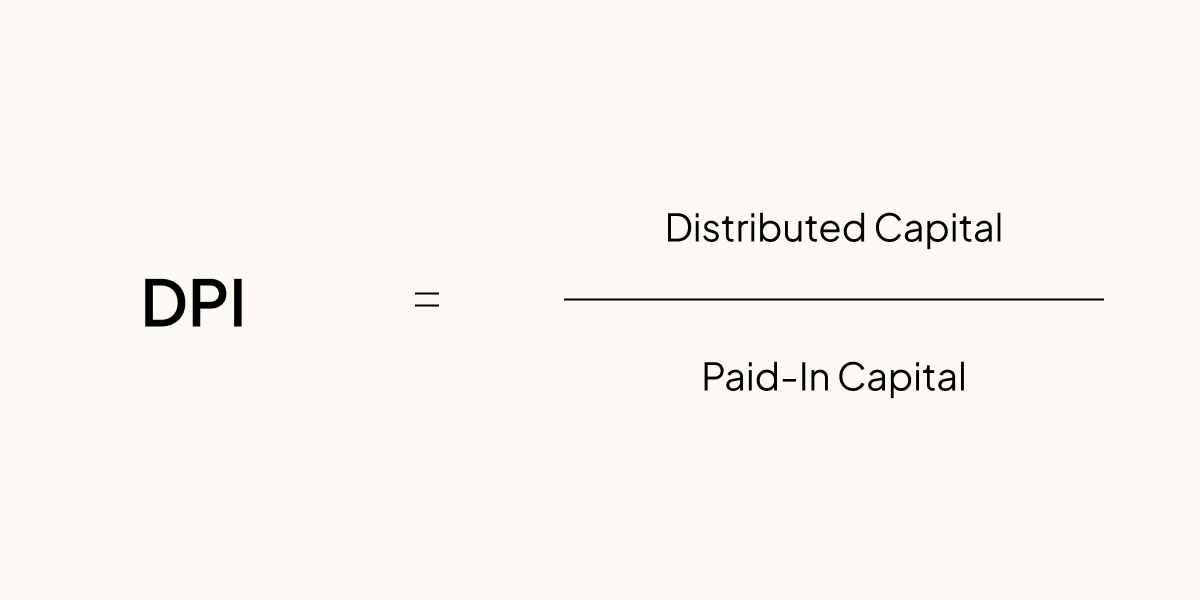

Distribution to paid-in capital (DPI)

DPI, or distribution to paid-in capital, measures the return multiple on the money paid into a VC or PE fund. That number does not change based on how long it takes to realize the investment. But unlike IRR, DPI does not take into account the book value of unrealized investments in a fund.