There are two main types of stock options that startups and other companies may offer as part of their employee compensation packages: incentive stock options (ISO) and non-qualified stock options (NSO). Companies may also offer different equity compensation types, like restricted stock awards (RSA) and restricted stock units (RSU). Each equity type is taxed differently by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). This article covers everything you need to know about NSOs.

What are non-qualified stock options?

Non-qualified stock options (NSO) are a type of stock option that does not qualify for tax-advantaged treatment for the employee like incentive stock options (ISO) do. NSOs can also be issued to other non-employee service providers like consultants, advisors, and independent board members. Unlike with incentive stock options, where you don’t pay taxes upon exercise, with NSOs you may owe taxes both when you exercise the option (purchase shares) and sell those shares.

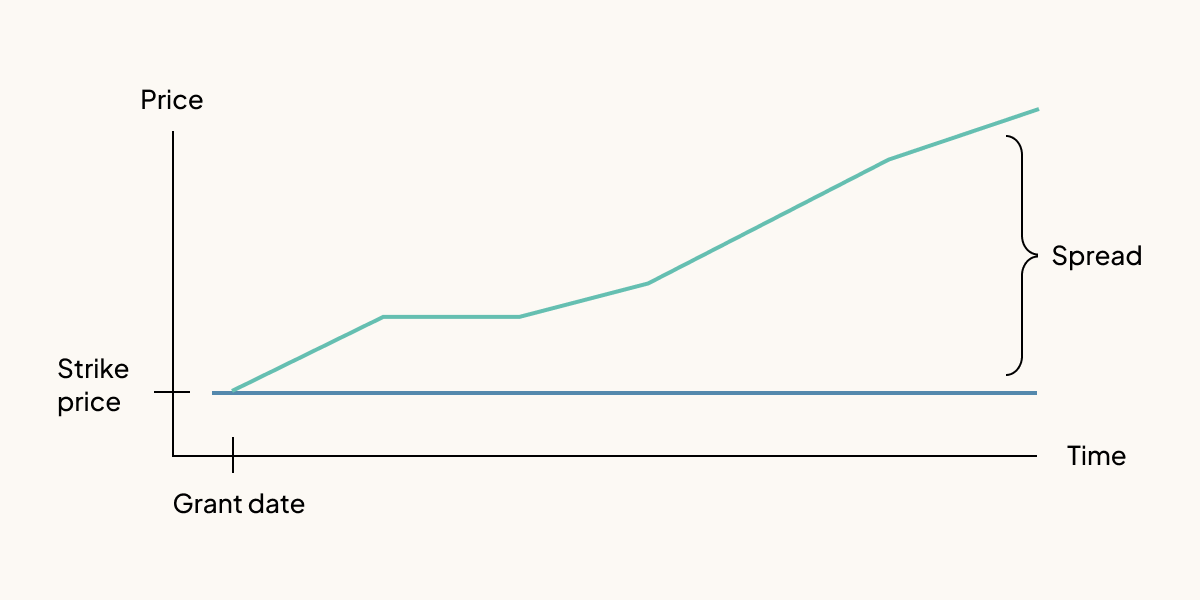

As with other types of stock options, when you’re granted NSOs, you’re getting the right to buy a set number of shares at a fixed price, also called the strike price, grant price, or exercise price. A company’s 409A valuation or fair market value (FMV) determines the strike price of an option. If the value of the share increases over time, you may make money on the difference (the spread) between your fixed purchase price and your eventual sale price.

How are non-qualified stock options taxed?

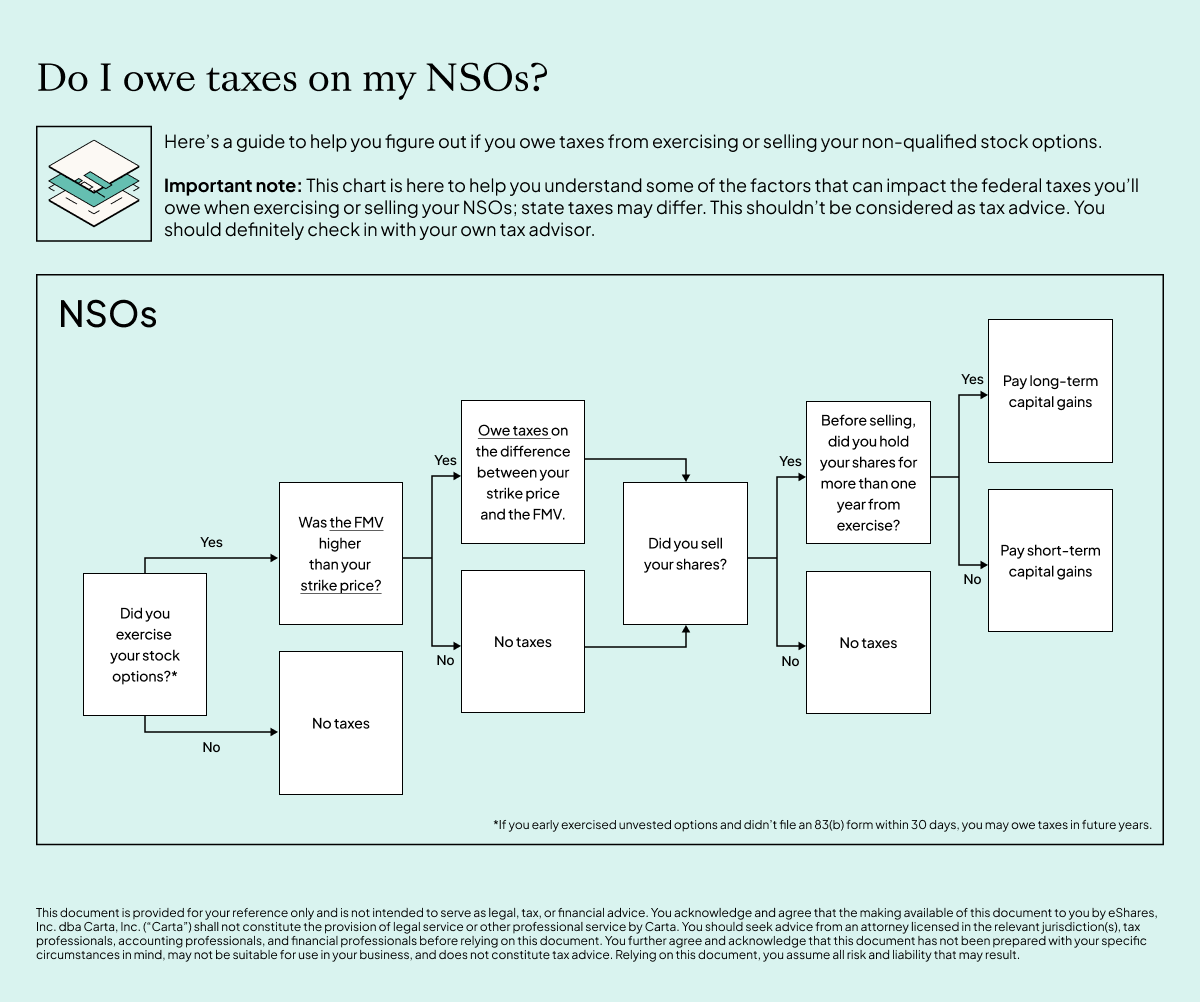

With NSOs, you may owe taxes both when you exercise your options and when you sell your shares. NSOs do not have the same tax benefits as other types of equity compensation.

→ Learn more about how taxes work for stock options.

When you exercise

When you exercise your stock options, you’ll be taxed on the difference between your strike price (fixed purchase price) and the current FMV of those stock options. This difference is the spread that we mentioned earlier. If you are an employee, your company will usually withhold ordinary income tax (which includes both payroll taxes and regular income taxes) on the spread when you exercise or may require you to pay the withholding tax out-of-pocket. If you are an independent contractor or other non-employee service provider, you will have to pay any applicable taxes directly to the IRS.

For example, if you exercise 100 vested options at a grant price of $1 and the current value is $2, you’ll owe ordinary income tax on the $100 gain.

When you sell

After you exercise your options, you can either sell right away or hold onto your stock. If you sell right away at the current FMV of the stock, you will not have any capital gain and will only have to pay ordinary income tax on the spread.

If you sell your stock within a year of when you exercised your options, you’ll pay short-term capital gains tax on any increase in value since the exercise date. But if you hold onto your stocks for more than a year and then sell, you would pay long-term capital gains tax, which is typically a lower rate than the short-term capital gains tax rate.

The qualified small business stock exclusion

After you exercise NSOs and hold stock, it may be eligible for the qualified small business stock (QSBS) tax benefit. If you qualify for QSBS, you could potentially sell your stock without owing taxes at sale if you hold your stock for at least five years.

After the five-year holding period, you can potentially exclude up to 100% of capital gains from their federal taxes when you sell the QSBS stock in a liquidity event such as a tender offer, secondary transaction, or initial public offering.

|

Action |

Tax implication |

|

You exercise your NSOs into stock |

You’ll likely owe ordinary income tax on the difference between your strike price and the current FMV of the stock |

|

You exercise NSOs and sell your stock in one transaction |

You’ll likely pay ordinary income tax on the difference between your strike price and the current FMV of the stock. If your sale price is higher than the company-determined FMV of the common stock, you could owe short term capital gains tax on the difference. |

|

You sell your stock within a year of exercising your NSOs |

You’ll likely pay short-term capital gains taxes on the profit you made selling your options |

|

You sell your stock after holding it for over a year after exercising your NSOs |

You’ll likely pay long-term capital gains taxes on the profit you made selling your options |

|

You sell your stock after holding it for over five years after exercising NSOs |

You may be eligible for the QSBS exclusion and could potentially owe zero federal capital gains taxes on the profit you made when you sell (up to a $10M cap and depending on your company’s QSBS status at the time you exercised your option) |

When can I exercise non-qualified stock options?

Typically, you gain the ability to exercise your stock options on a set schedule as you work for a company over time. This is called vesting. You can exercise your NSOs as soon as they vest, but you can also choose not to exercise.

If you choose to exercise, you can either pay the strike price in cash or, if your company allows it, sell a portion of your shares to cover the cost of exercise (referred to as a “cashless” exercise). Check to see if your company allows cashless exercises.

If you leave your company, you’ll usually have a certain period of time—the post-termination exercise period (PTEP)—to exercise your vested NSOs. If you don’t exercise your options before this period ends, you’ll lose your opportunity to purchase them.

To maximize your potential profit after taxes, talk to a tax advisor before exercising and selling your non-qualified stock options. While advisors can’t predict your company’s future stock performance, they can help you understand your next steps and minimize your tax liability.