Every startup has a budget. At some level, the question of how much a venture-backed company can spend depends on two factors: How much capital it has already raised, and how long it will wait before raising capital again.

When round sizes are high and the wait between venture rounds is short, companies tend to have more money to spend more quickly on things like hiring, advertising, and new products. This was the case during the white-hot venture market of late 2020 and early 2021. But when round sizes are low and the wait between rounds is long—as has been the case through late 2022 and 2023—companies have less money to spend. They have to tighten their belts.

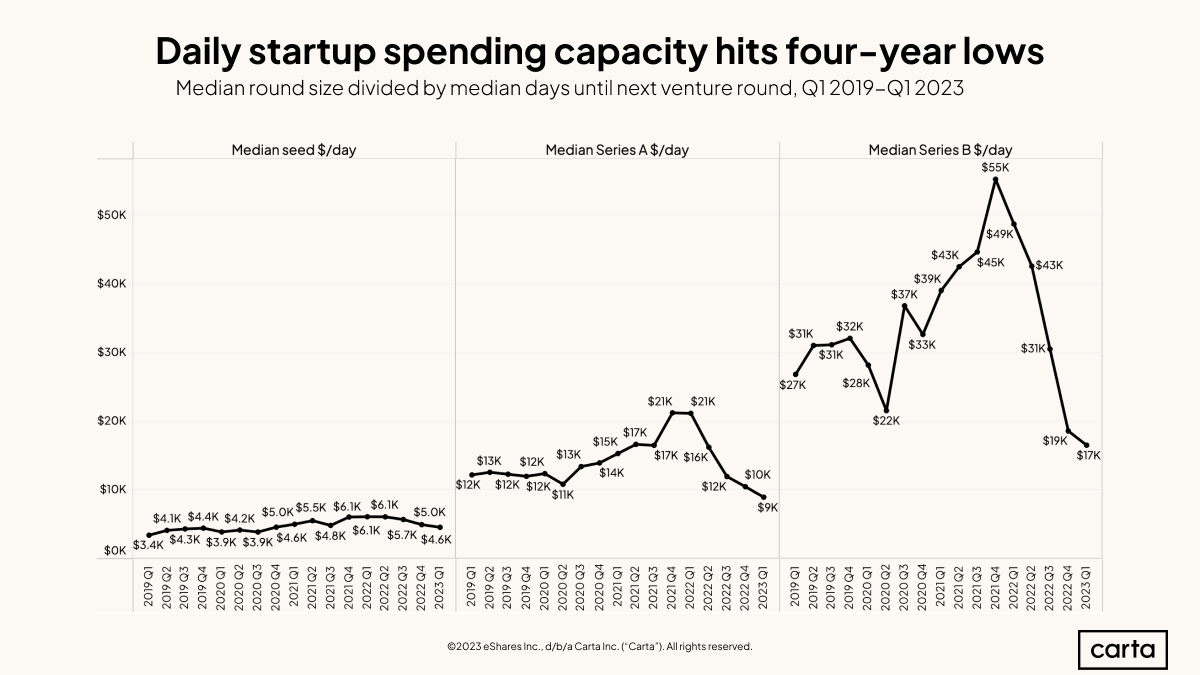

We can use those two variables—venture round size and the time between venture rounds—to create a rough measurement of the spending rate that startups at various stages might be able to sustain before running out of cash. In Q1 2022, for example, the median Series A round was $12 million, and the median interval between a Series A and Series B was 566 days. Divide the former by the latter, and you get a ratio of $21,201 per day, or about $645,000 per month.

By Q1 2023, things looked very different. The median Series A sank to $6.4 million, and the median wait time until the next round climbed to 714 days. That divides out to just $8,964 per day in startup spending capacity, or about $273,000 per month—less than half the rate of a year prior.

Year over year, spending capacity is down 25% at seed, 57% at Series A, and 65% at Series B. At both Series A and Series B, this measurement fell to its lowest point of the past four years in Q1. At seed, it reached its lowest point since 2020.

These figures are not an exact depiction of startup runway or burn rate—in reality, budgeting a startup’s spending is more complicated, and there are other potential sources of capital besides a venture round, such as venture debt funding, raising a SAFE, or generating revenue. Directionally, however, they paint a clear picture of how the current fundraising environment has shifted over the past several quarters, forcing early- and mid-stage startups to change their spending plans and stretch each dollar further.

How startups are streamlining

At some level, this shift in the market over the past year has made life more difficult for early-stage founders. But for young startups in particular, investors believe it may be a blessing in disguise.

“You’d think extra money is good for a company. But our view is, it’s not,” says Jon Keidan, founder and managing partner at consumer-focused venture firm Torch Capital. “The truth is that you need to be focused. If you have too much money, you can build all these things and still have quite a bit of runway. But it’s not necessarily getting you to the key thing. And so the advantage of less money and less people is it forces you to always focus on the key thing.”

Marcos Fernandez, managing partner at fintech investor Fiat Ventures, framed this change as a welcome shift in priorities. When money was easier to raise, he says, the startup industry’s ethos was to achieve growth at all costs. Now, it’s more about establishing product-market fit and positive unit economics as early as possible.

“The lack of capital out there has forced both investors and founders to be more diligent about how they think about building businesses,” Fernandez says. “And that’s a really positive thing.”

Trimming expenses

How are startups slimming down? Keidan and Fernadez agree that an increased focus on the main idea means many startups are cutting spending on non-core projects and secondary business lines. Many others have laid off workers or reduced plans for hiring growth. In terms of budgeting, the two investors say they’ve advised early-stage startups to be cautious about spending too heavily on marketing or sales before establishing a firm product-market fit. In some cases, CEOs are taking a pay cut to help conserve cash

There are other areas where trimming costs isn’t an option.

“If you’re just starting out, you’ve got to be spending on R&D and product,” Keidan says. “That’s the core of what you’re selling.”

A new seed strategy

In addition to reducing spending and reallocating resources, this combination of smaller round sizes and longer waits between rounds is causing companies and investors to reconsider fundraising timelines and strategies.

A growing number of startups are raising SAFEs or convertible notes as an alternative to priced rounds, allowing them to bring on new capital without resetting their valuations. Smaller round sizes are driving another trend at the seed stage, Keidan says: He’s seen more startups raise an initial seed round, then follow it up with an extension after they begin to gain initial traction.

“[A seed round] used to be enough to get you to an A round, but I’m not sure that’s the case anymore,” Keidan says. “If it’s going well, then investors will come together and do an extension, probably at a higher valuation. That could be another $1 million or $2 million. And then between those two tranches, ‘seed’ really becomes a phase, and not just a round.”

Setting the stage for growth

Fernandez believes having less capital to work with can be beneficial during a startup’s early days, forcing it to focus on core problems. But his overall optimism about the current state of the market is predicated on the idea that, sometime in the not-too-distant future, round sizes and valuations will again start trending back up. Then, those same startups with strong unit economics and product-market fit will be positioned to take advantage.

The financial crisis and Great Recession of the late 2000s birthed a generation of unicorn startups that capitalized on a decade-long bull market in the 2010s. The current venture downturn might someday have a similar legacy.

“Over time, we’re gonna get back into a normal market cycle,” Fernandez says. “As we think about things expanding again, those companies in that moment that already have really good business models—they will be hitting those Series As and Bs, and people will then have capital that they want to really throw at them. And they can really accelerate out of that.”

When that shift from market contraction to expansion will occur, of course, is still anyone’s guess. For now, the mission for startups is to survive—no matter how far they have to stretch their hard-raised dollars.

“Hope for the best, prepare for the worst. And if that means it’s another 24, 36, 48 months, that’s what it is,” Fernandez says. “The idea is to just keep yourself in the game for a little bit longer.”

Get weekly insights in your inbox

The Data Minute is Carta’s weekly newsletter for data insights into trends in venture capital. Sign up here: