Keeping track of tax obligations isn’t most people’s idea of fun, but if you’re earning equity, you need to know what types of tax you’ll owe—and when you’ll need to pay them. Having a solid understanding of how equity is taxed will help you make smart decisions as you earn equity, exercise your options, and sell your shares.

This article will run through the basics of equity taxation and help you determine whether your shares qualify for any preferential treatment—usually in the form of lower tax rates. We’ll also walk you through some steps to avoid the common mistake of paying the same tax twice on exercised options. That’s important if you’ve recently sold shares on the public market or as part of a secondary liquidity transaction (like a tender offer or a Carta Cross auction).

Important note: While we’re here to help you understand how taxes on stocks work, we aren’t giving tax advice in this article. You should definitely check in with your own tax advisor.

What triggers taxes on equity?

Two taxes generally apply to employee equity earnings: ordinary income tax and capital gains tax. Typically, you’ll owe income tax on your equity in the tax years during which you acquire shares. Capital gains tax comes into play when you sell your shares. (A third tax, the alternative minimum tax (AMT), may also apply to certain equity earners. We’ll talk more about that later on.)

Three major milestones can trigger a tax liability: equity vesting, exercising your options, and selling your shares.

1. Vesting restricted stock

Vesting refers to the process of earning an asset as you meet certain conditions. Usually, these conditions are milestone-based or time-based—like completing a specific project or remaining an employee at your company for a defined amount of time.

With stock options, you vest the right, or option, to purchase your shares at a defined price (the “ strike price”), which is set by the company in your award letter. When you vest restricted stock, such as restricted stock units (RSU) or restricted stock awards (RSA), you take ownership of your shares as they vest.

Stock award vesting can either be single-triggered or double-triggered. Single-trigger awards require that you meet just one condition for vesting; typically, it’s an amount of time that must elapse from the date of the award. Double-trigger vesting requires that a second condition be met; usually, this is a liquidity event—such as a company IPO, acquisition, or secondary offering—that enables you to sell vested shares.

When you vest restricted stock, it triggers ordinary income tax on the fair market value (FMV) of the shares on the vesting date. This income tax is due by the filing of your tax return for the related calendar year. If you hold RSAs, you have the option to file an 83(b) election, which lets you pay income tax on your shares in the year you are granted the award. Be aware that this approach may trigger a tax payment before your stock has vested, and have other complications you should discuss with your tax advisor.

2. Exercising your options

Unlike RSUs, stock options, including incentive stock options (ISO) and non-qualifying stock options (NSO), must be exercised for you to acquire the stock. Exercising an option means buying the shares at the strike price. This must be completed before the option grant expiration date, or if you’ve left the company, before the end of the post-termination exercise window, discussed below. While the options to purchase may vest over time, you only acquire the stock when you exercise your options.

If you’re exercising NSOs, you will have to pay income tax on the difference, or spread, between the exercise price and the fair market value (FMV) of the shares at the time of exercise. This spread counts as ordinary income. While your employer will withhold taxes upon NSO exercise, your ultimate tax liability may exceed the withheld amount.

For ISOs, the spread between the strike price and FMV at time of exercise could subject you to the alternative minimum tax (AMT) for that tax year. (More on that below.)

If you’re planning on leaving a company, tax considerations might affect your decision about whether and when to exercise your shares. Many companies require former employees to exercise their shares during a post-termination exercise window, a limited (and usually short) period of time following an employee’s departure. Many employees end up forfeiting their options because they haven’t planned ahead for how they’ll pay the exercise price or the income taxes due on the stock award.

Post-termination exercise windows are typically 90 days, but your equity plan should have more details. At Carta, we’ve seen trends of extended post-termination exercise windows as a more employee-friendly benefit. But even in cases where the window is longer than 90 days, there is another consideration: 90 days following an employee’s departure from the company, ISOs are disqualified from special tax treatment under current IRS rules, and are converted to NSOs. If you have ISOs, this means that even if your company permits a longer post-termination exercise window, waiting longer to exercise will change your tax circumstances.

By helping private companies organize regular liquidity events for current shareholders to sell their equity, Carta Liquidity makes it easier for employees of participating companies to overcome difficulties imposed by the post-termination exercise window. Through these liquidity mechanisms, employees can meet double-trigger vesting schedules, if applicable, and sell their shares. The proceeds from these sales can help employees meet the costs and tax obligations of exercising more stock later on, such as when they leave their company.

3. Selling your shares

You may owe ordinary income tax or capital gains tax when you sell your stock. The amount you’ll pay in capital gains depends on the type of equity you hold.

Ways you may be able to pay less in taxes on your equity upon sale

The qualified small business stock (QSBS) exemption

Whenever you receive an award for private stock, one of the first things you should determine is whether you can qualify for preferential tax treatment through provisions in the current tax code that incentivize investment in small businesses, known as the QSBS exclusion.

If you hold qualified small business stock (QSBS), you may be entitled to a reduced capital gains rate for federal taxes on the sale of your stock—possibly as low as 0%. To take advantage of QSBS benefits, you need to meet two basic criteria:

-

The company that issued you stock must have been a qualifying small business at the time you acquired your shares. Remember, if your company issued you equity in the form of stock options, you’re not considered to have acquired your shares until you exercise those options. For RSUs and RSAs, acquisition occurs when your shares vest, unless you’ve made a valid 83(b) election, as discussed below. Your company should be able to confirm the QSBS status of your shares.

-

You’ve held your stock for at least five years since the acquisition date.

These criteria can help you determine when to exercise your options, because early exercise means you’ll complete the five-year holding period sooner. They can also help you decide whether to file an 83(b) election, if your plan permits early exercise, because filing an 83(b) election will also start the clock on the holding period.

83(b) elections

If your equity plan allows early exercise, you can pay taxes on your shares at the time of the early exercise, as opposed to at time of vesting, by making an 83(b) election. ISOs ordinarily vest over time. But if you exercise your ISOs early, when there is no difference between the strike price of the ISO and their current FMV, filing a timely 83(b) election may allow you to avoid AMT impact for the ISO exercise and start the clock on the holding period for your shares.

83(b) elections are also possible for RSAs.

There are three principal reasons to make an 83(b) election:

-

You expect the fair market value of the stock to increase between grant date and vest date of your shares.

-

You want to start the holding period of your qualified small business stock (QSBS) shares.

-

You want to start the holding period for capital gains treatment upon eventual sale.

It is crucial that the shareholder file the 83(b) election directly with the IRS in a timely manner: Current rules require you to file no later than 30 days after the early exercise. Otherwise, the tax benefits are forfeit.

Qualifying dispositions on ISOs

If you hold ISOs, you might be able to save significantly on your tax liability at the point of sale by ensuring that you meet the criteria for a qualifying disposition. Meeting these requirements will entitle you to the lower, long-term capital gains rate on your ISO-related gain. To qualify, you must hold the shares for the longer of:

-

Two years after your ISOs were granted

-

One year after exercising your ISOs

As with QSBS, understanding the timeframes for determining a qualifying disposition on ISOs will help you choose when to exercise or sell your shares.

Planning for the alternative minimum tax (AMT)

Another thing to consider when exercising your ISOs is the alternative minimum tax (AMT). This tax limits the size of tax benefits on ISOs past a certain exemption amount, which changes every year to account for inflation. (It was $73,600 for individuals or $114,600 for married filing jointly in 2021.) For high-income individuals and married couples, AMT exemption begins to phase out at $523,600 for individuals and $1,047,200 for married couples filing jointly in 2021.

To calculate your AMT, you make adjustments to your taxable income based on instructions set by the IRS on form 6251. One of those adjustments is the spread between the FMV and exercise price of ISOs exercised and held through the end of the year. To the extent that your minimum tax is greater than your regular tax, the difference is tacked on as AMT on page 2 of your 1040. In other words, you’re paying whatever’s greater: your minimum tax or regular tax.

Because you’re entitled to the AMT exemption every year, you may find it worthwhile to space out your ISO exercises over multiple years. (You may also be eligible to receive a credit for AMT paid in a previous year.) Since this strategy may not be advantageous for everyone, you should consult a financial tax advisor before making your decision.

Stepping up your tax basis

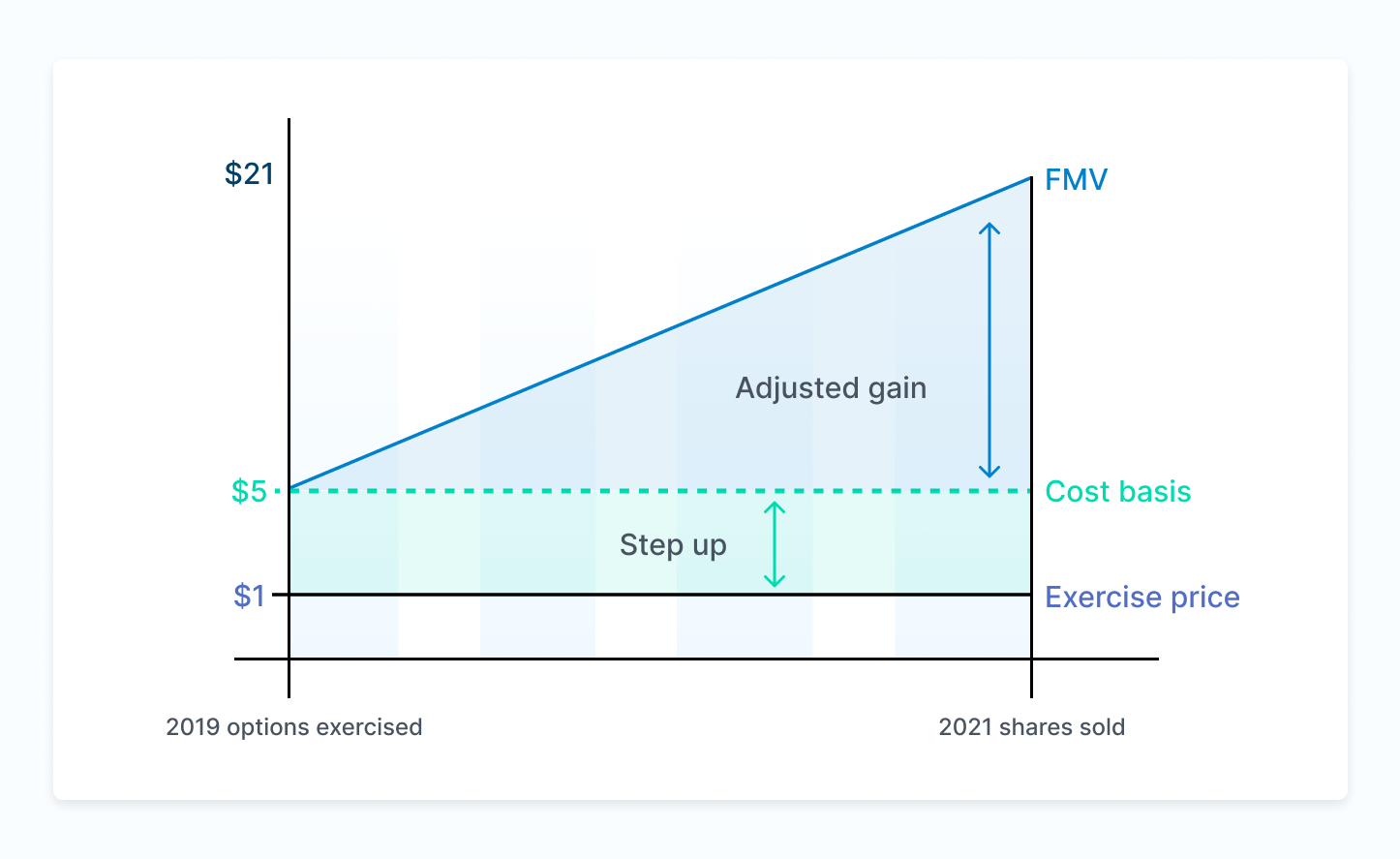

One of the most common mistakes that taxpayers make is the failure to step up their tax basis when selling their equity. In practical terms, stepping up means taking credit for the tax you’ve already paid on the equity you sell.

For example, let’s say you have 100 non-qualified stock options (NSOs) that you exercised in 2019 at a $1 strike price, when the FMV of the stock was $5. At that point, you would have paid tax on $4 of income per share: the difference between the FMV and strike price. While your cost basis, or the amount you paid for the stock, is the $1 strike price, your stepped-up tax basis, or the amount on which you’ve already paid tax, is $5.

Now let’s say it’s 2021, and you’re selling your stock. You’ll want to be sure to include a $5 cost basis on your individual tax returns. By doing so, you’re avoiding paying tax twice on the $4 of income per share that was already taxed in 2019.

The tricky part is that your 2021 form 1099-B will reflect the $1 actual cost basis, and you’ll have to “step up” that extra $4 per share as an adjustment to gain (or loss) on Form 8949, which is part of Schedule D. Keeping good records that reflect your FMV at time of exercise will help you corroborate your stepped-up cost basis.

Maximize your gains by planning ahead

It’s exciting to work for a company that offers equity compensation. However, many tax-related rules can be tricky to navigate. You should always consult with a tax advisor before selling your shares.

For a more detailed walkthrough of taxes on employee grants, take a look at our explainer on how stock options are taxed. And if you’re planning to sell shares through Carta Liquidity, you’ve got help. You can use the Carta Liquidity Tax Guide for Sellers to learn some more of the tax terms, understand your withholdings, and prepare to meet your tax obligations.

Armed with the right information, you can be sure you’re not leaving money on the table—or paying more than what you owe.

Give your employees support in their tax decisions

Carta Equity Advisory helps the employees of our customer companies make informed decisions about equity ownership and taxes.