Overview

The startup ecosystem is a massive engine of financial power and opportunity for founders, employees, and investors. But not everyone has had the opportunity to participate in this ecosystem.

We partnered with #ANGELS in 2018 to report on equity distribution. Every year since, Carta has been committed to creating a new report and to gathering the brightest minds in venture and entrepreneurship around the need to close this gap.

We have an opportunity to expand that ecosystem, together—to bring more ownership opportunities to more people.

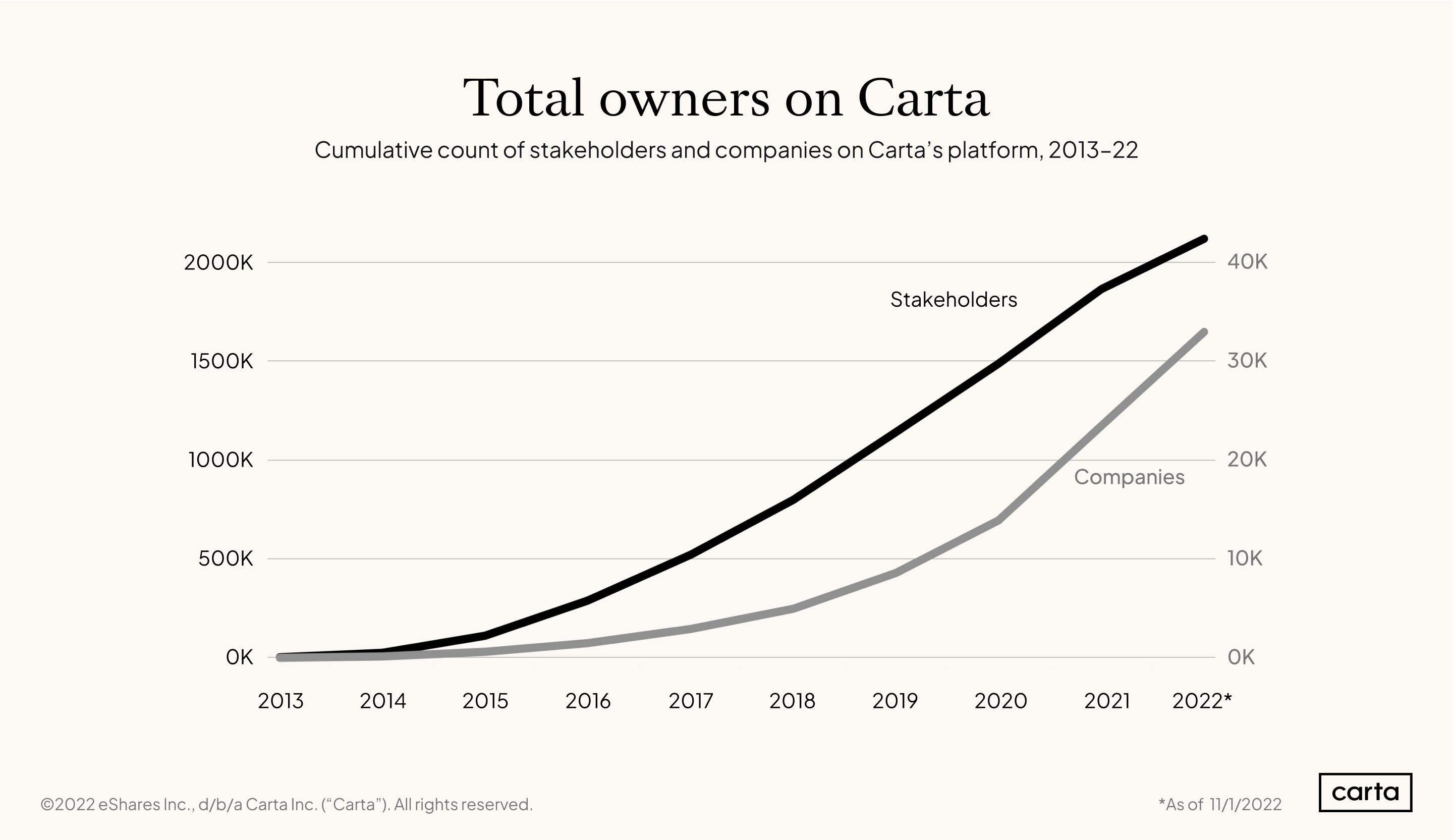

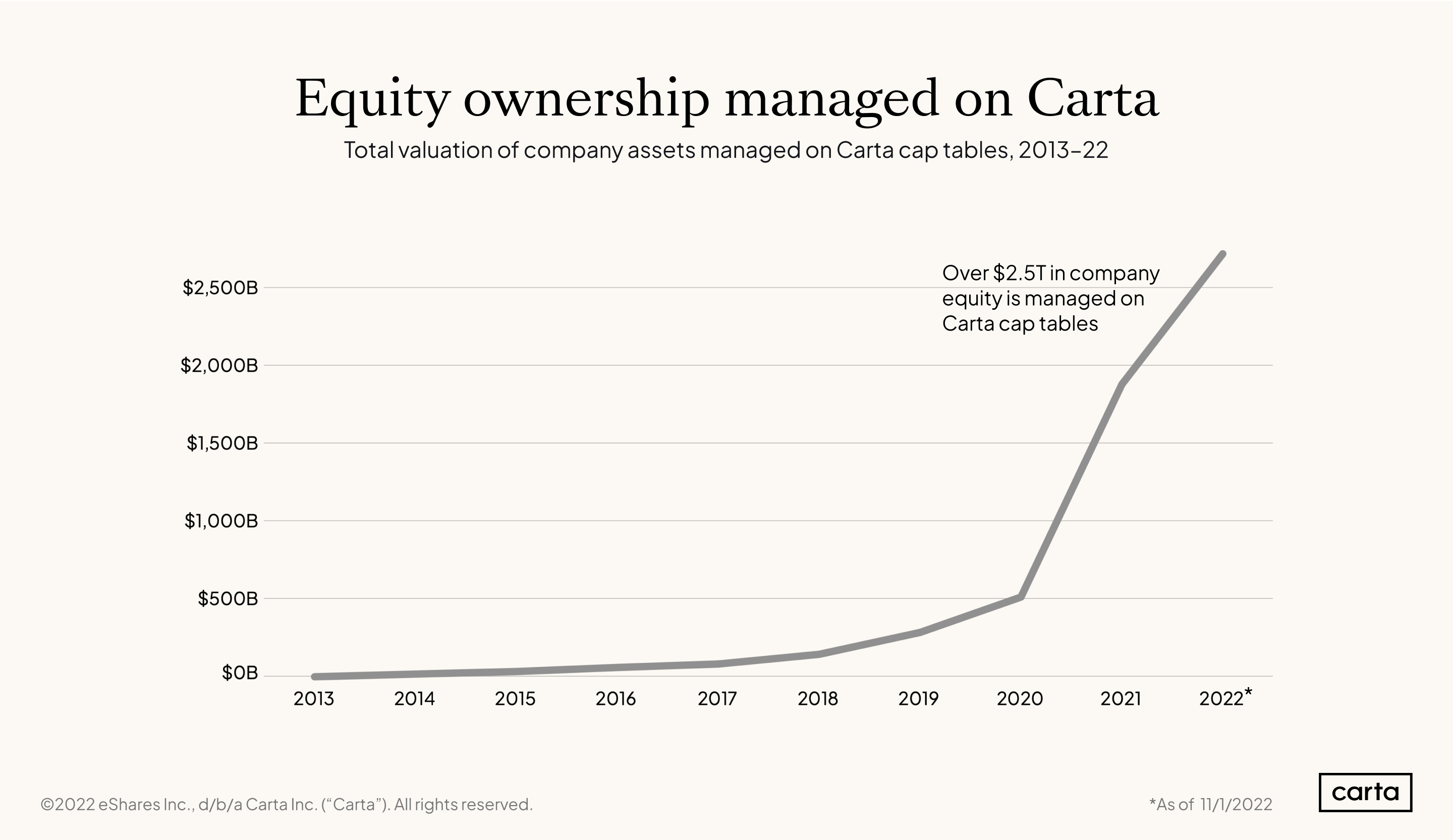

With more than 30,000 companies and over $2.5 trillion in assets on the Carta platform, we have a unique window into a massive dataset about startups and venture capital, and an opportunity to increase transparency.

It is only by knowing who makes up this ecosystem—who gets equity compensation? Who is founding companies? Who has the chance to invest in venture funds and startups?—that we know who is left out of these opportunities for ownership, and how we can change that, together.

What’s new this year

For the first time, we’re able to share expanded geographic data—to see where in the United States people are more able to participate in the startup and venture ecosystem, and how various metro areas compare.

We’re also able to look at parenthood, how it affects employees and founders, and how the impacts vary by gender. When it comes to gender, we were able to expand this year to include data about nonbinary people. Although our sample sizes weren’t sufficient to include this group in every gender metric, we’ve shared this data wherever it was possible.

We looked at investor demographics for the first time, including the geography of venture capital firms, and the gender, race, and ethnicity of limited partners.

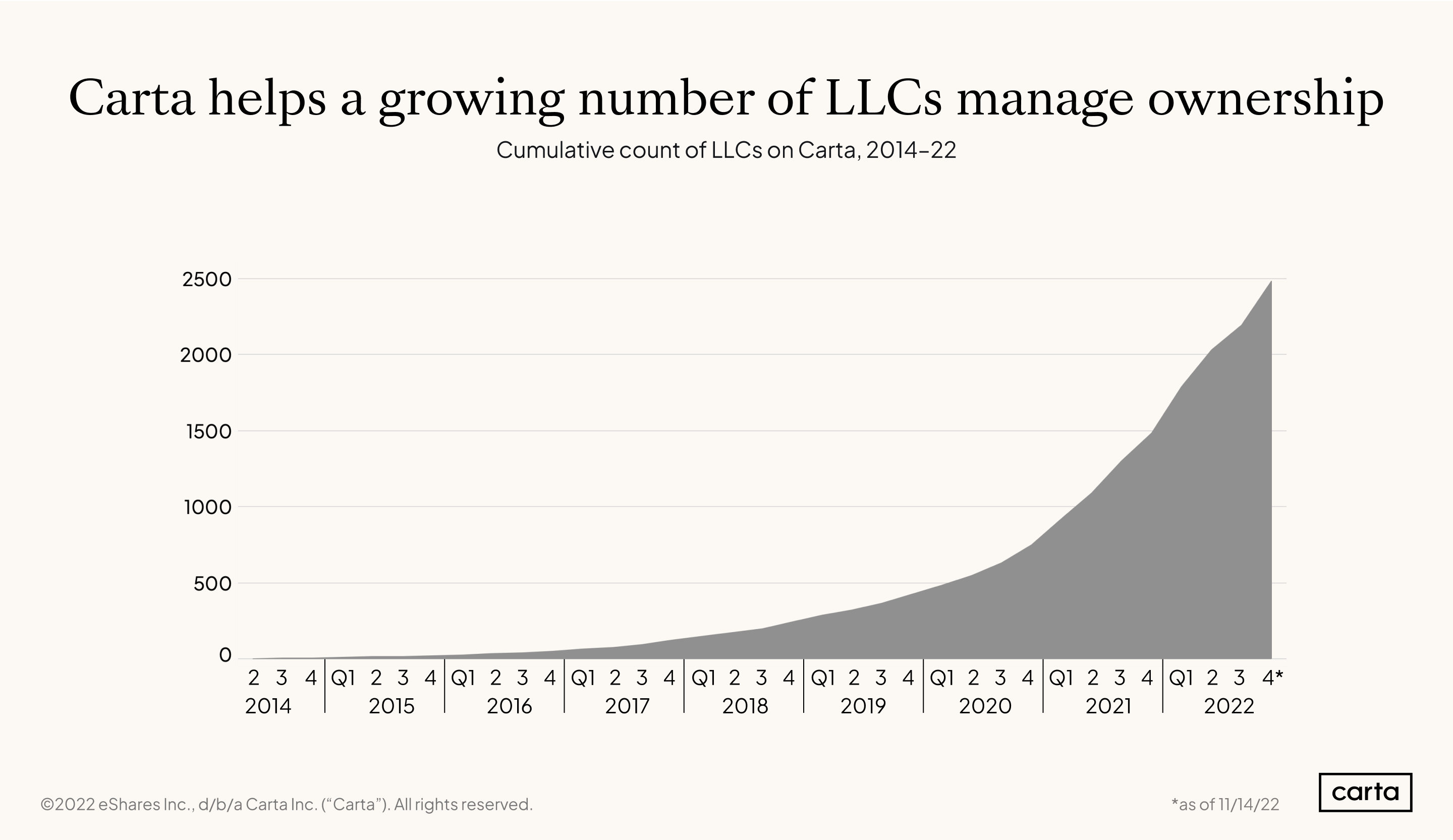

Finally, this year we are able to glimpse beyond traditionally venture-backed companies. While the rest of this report looks at corporations that issue stock shares, there are also more than 2,000 limited liability corporations (LLCs) on the Carta platform. LLCs have different geographic and industry patterns than traditional corporations, and are increasingly issuing LLC-specific types of equity on Carta. We’re thrilled that more types of businesses are embracing the ownership economy, and we’re glad to begin to include more company types in the report this year.

Employee ownership

Throughout this report, we analyzed equity value using notional value, defined as the fair market value per share at the time of the grant multiplied by the number of shares in the grant. We’re using this metric because our focus is on how companies choose to reward employees. This metric does not reflect the uncertain and potentially much higher value that an employee may eventually be able to realize from their equity, which depends on the trajectory of the company’s valuation and opportunities for liquidity.

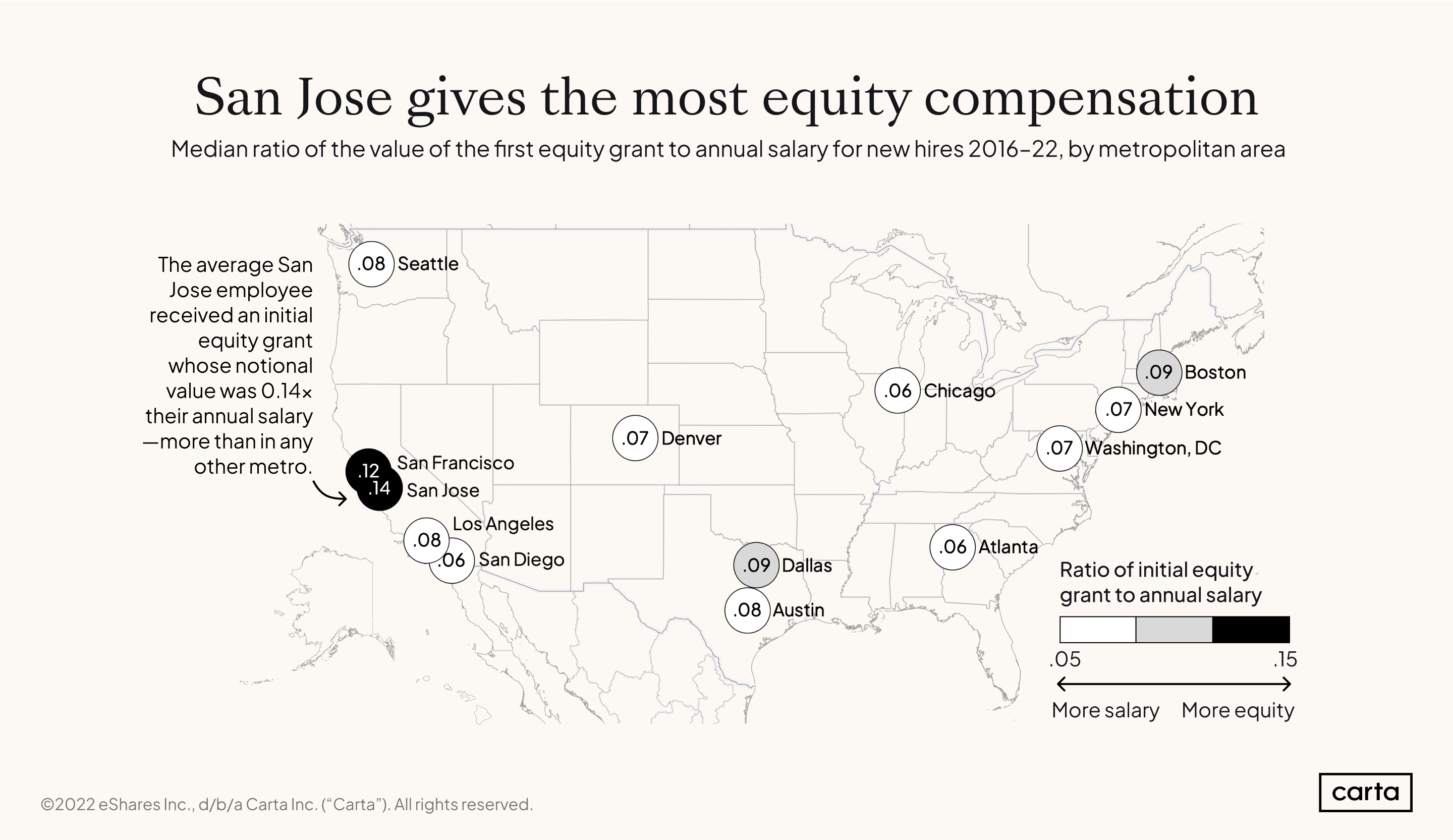

Where do employees get equity?

Silicon Valley still grants the most equity to its employees. We looked at the makeup of compensation packages and compared the notional value of each employee’s first (or initial) grant of stock options, which typically vest over four years, to their annual salary by metro area.

San Jose had the highest median ratio, with the average employee receiving an initial equity grant whose value was 0.14x their annual salary. With a median salary of $150,000 in San Jose, this would be a notional value of $21,000.

In contrast, Atlanta had the lowest median ratio, with the average employee getting an initial equity grant that was 0.06x their annual salary. The median salary in Atlanta was $100,000, and 0.06x this amount would be $6,000, for notional value of equity.

A number of cities (Miami, Boston, Washington, DC, Seattle, Salt Lake City, San Diego, and Denver) saw an increase in the ratio of equity to salary when comparing 2019–20 to 2021–22.

Who gets equity, by race and gender?

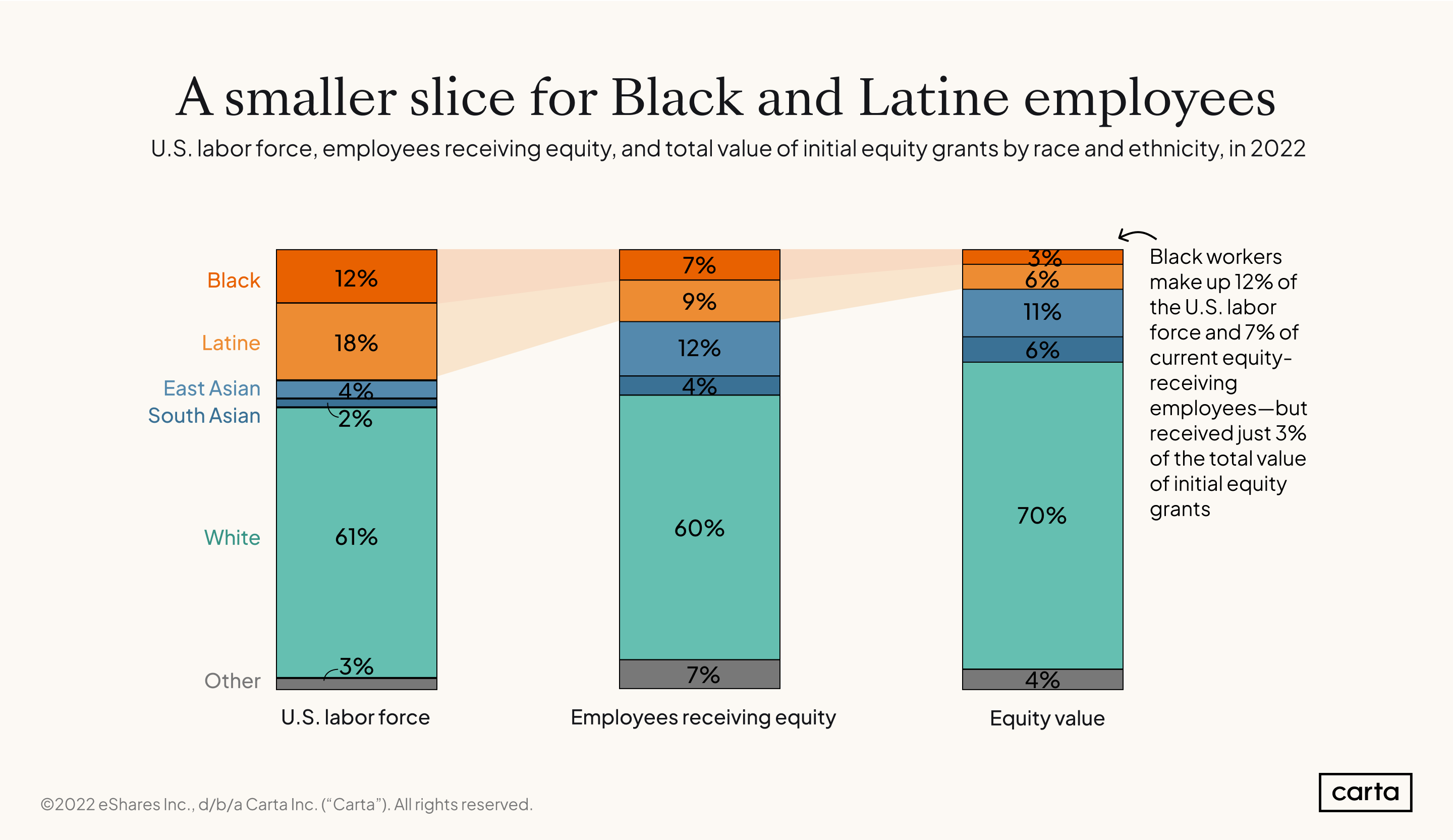

When looking at equity grants by demographics, we zeroed in on what’s happening this year. While Black and Hispanic & Latine 1 people make up 30% of the U.S. labor force, only 16% of equity-receiving employees in 2022 are Black or Latine. Collectively, these Black and Latine employees were granted only 9% of the total notional value of initial equity grants. Despite efforts to improve racial parity in tech, especially since 2020, these numbers have not budged much since last year.

In contrast, 61% of the U.S. labor force is white. This group comprises 60% of employees who were granted equity, and they collectively received 70% of the total value of initial equity grants. East Asian and Southeast Asian 2 employees make up 4% of the workforce and 12% of those granted equity in 2022. Meanwhile South Asian 3 people are 2% of the workforce and 4% of those granted equity. Unlike with white employees, the proportion of notional value granted to Asian employees—17%—was consistent with the percentage of those granted equity at 16%.

The percentage of new hires self-identifying as Indigenous American, Middle Eastern, Pacific Islanders, and mixed backgrounds are grouped together here as “Other” because their numbers are too few separately.

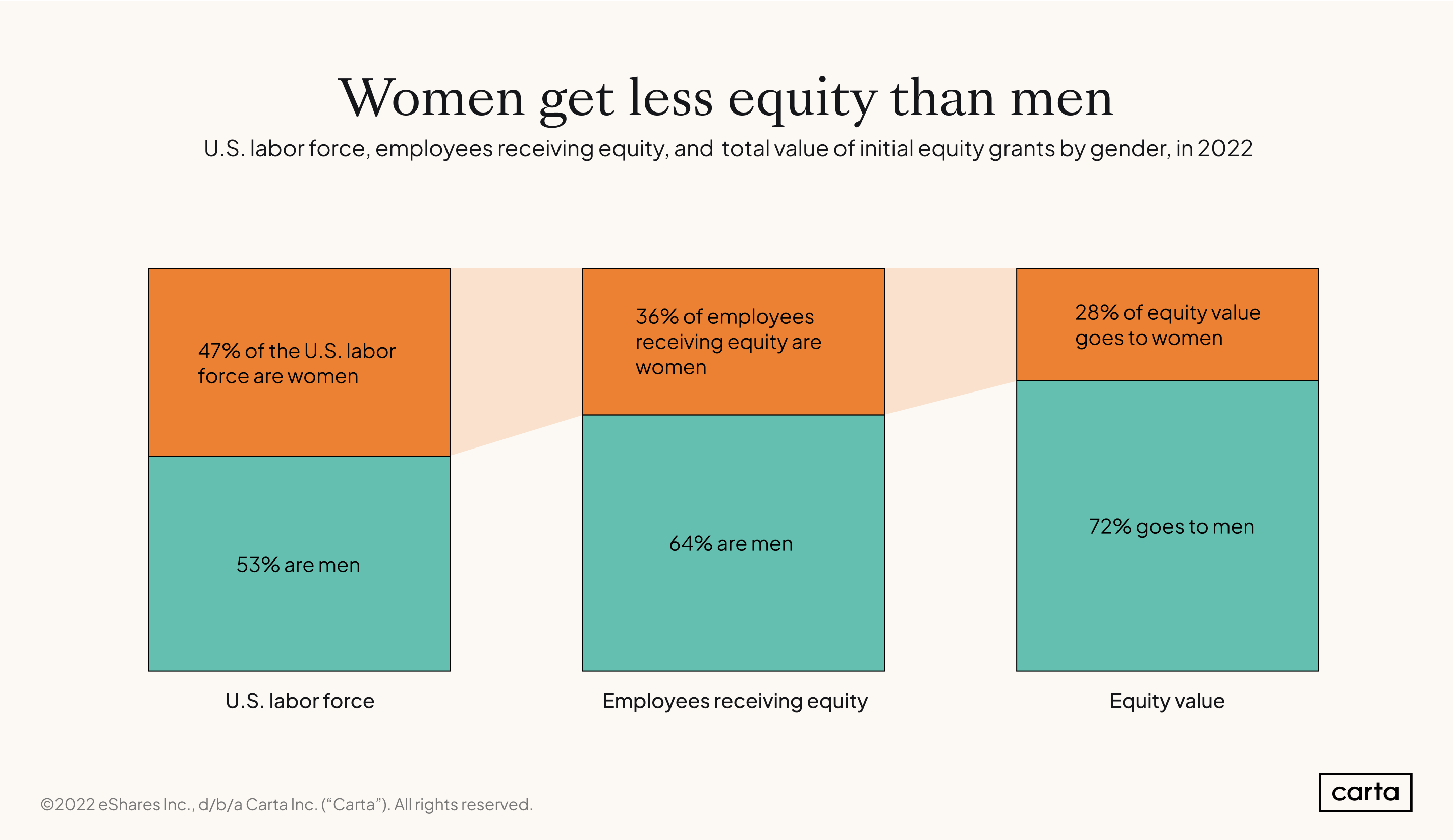

Women receive less equity compensation than men do. While women make up 47% of the U.S. labor force, they comprised just 36% of equity-receiving employees in 2022. Collectively, they received 28% of the notional value of initial equity grants.

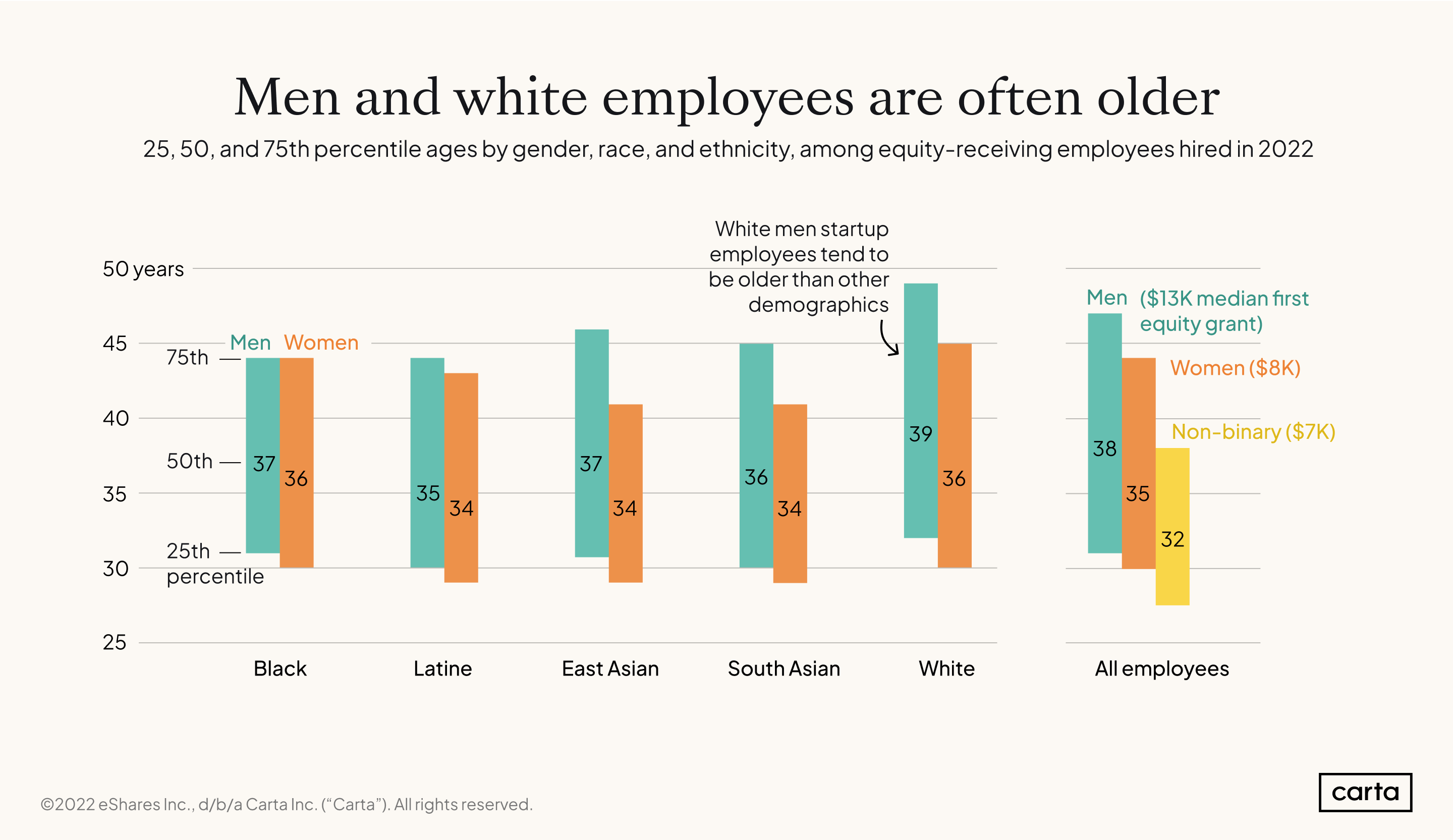

Across genders, white employees receiving equity tended to be slightly older than other groups hired in 2022. Within each race and ethnicity, men were slightly older than women. People who self-reported their gender as nonbinary tended to be younger than those who self-reported as either men or women. This age difference may be partly due to generational differences in how gender is approached and expressed.

The age difference may underpin part of the overall equity disparities between white men and other groups. But the age difference is relatively small and unlikely to fully explain the size of the equity gaps. Inequities still persist when comparing equity within age groups.

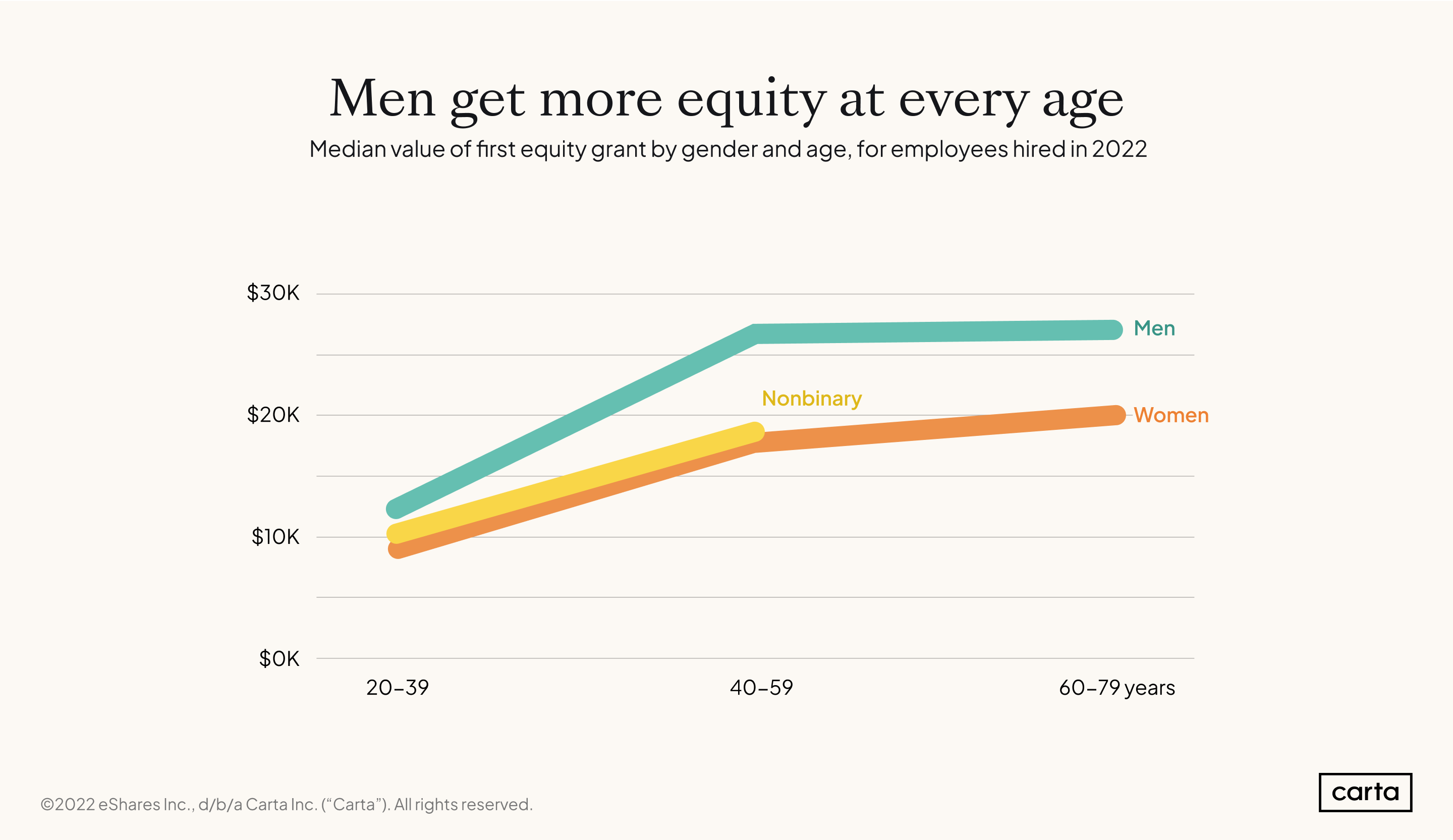

Across all ages, men received more equity than women or nonbinary people in 2022.

In general, nonbinary employees received comparable equity value to women. About 1% of employees on Carta who completed their demographic profile shared that they are nonbinary 4 —meaning that their gender doesn’t fit within the binary of “man” or “woman”; and a smaller percentage elected to self-describe their gender. Some ways people self-described their gender included “genderqueer,” “she/they,” “male/nonbinary,” and “ two-spirit,” a term used by some Indigenous people.

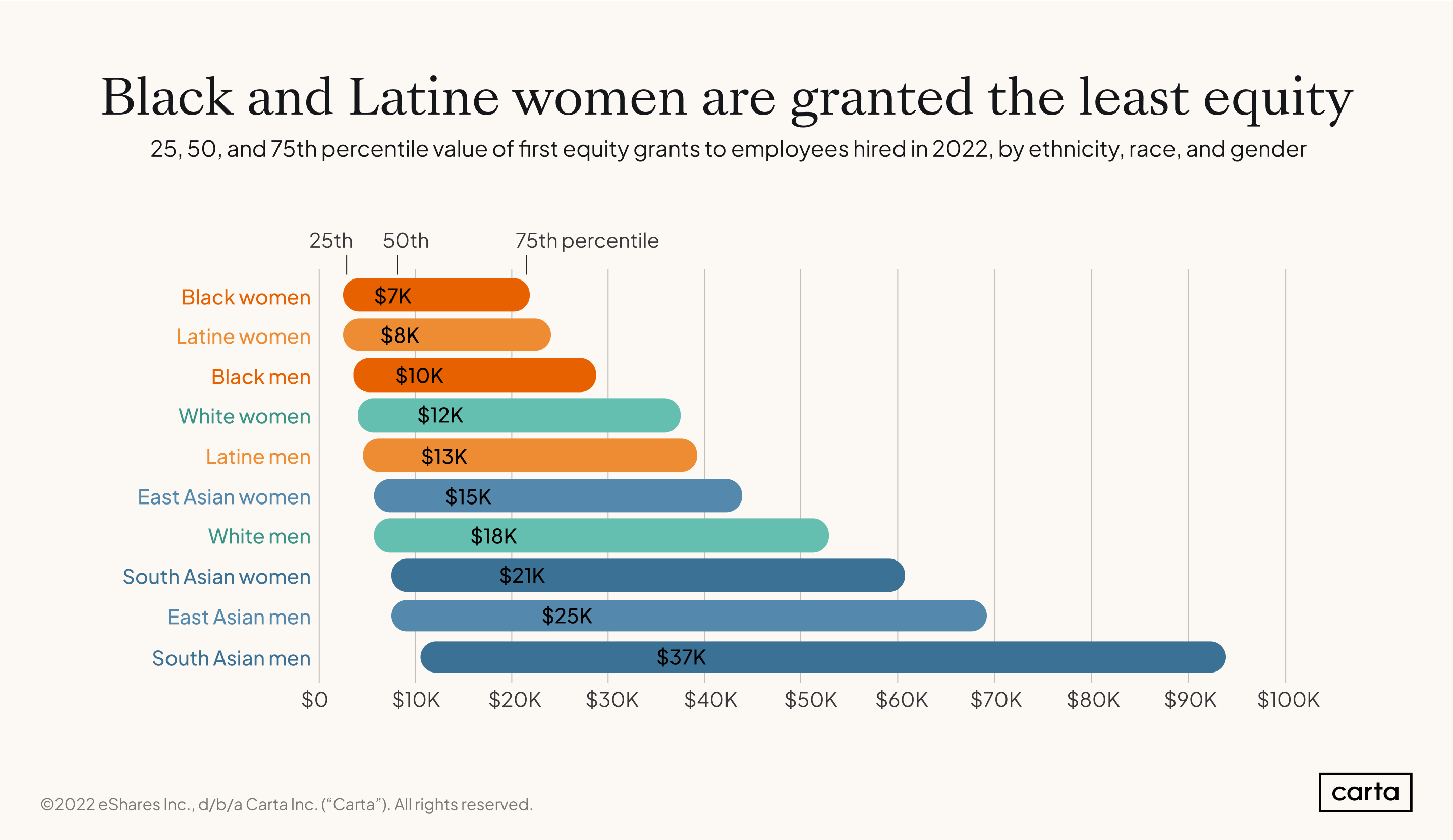

The intersection between gender and race and ethnicity provides a more detailed picture of disparities in equity compensation. In all race and ethnicity groups, the median amount of equity granted to men hired this year was higher than for women. Black women received the lowest median value of equity grants, while South Asian men received the highest median value of grants.

Parenthood

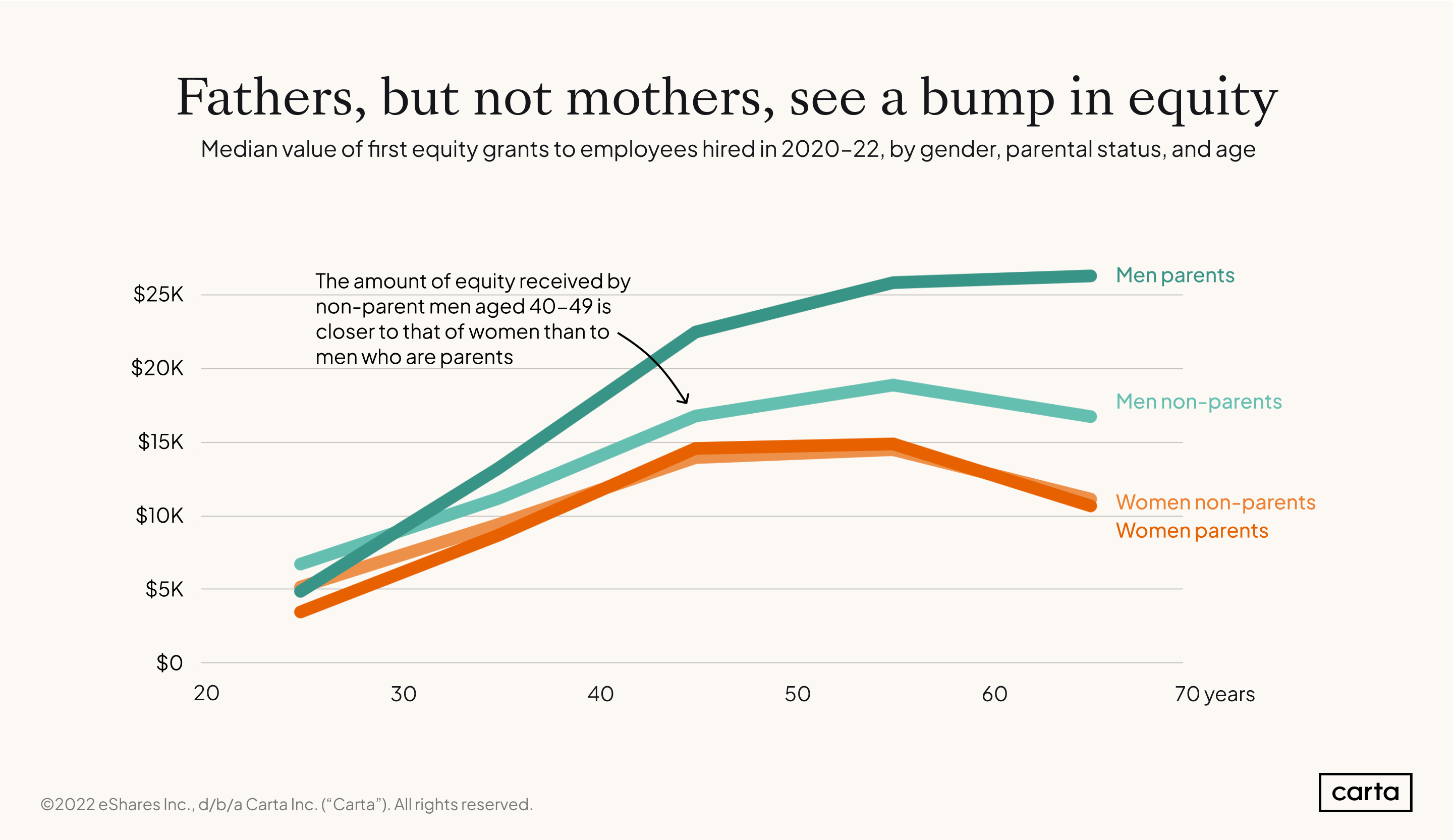

The well-researched pattern of men with children seeing a “fatherhood premium” in salaries also holds true with equity compensation—fathers tend to receive a bump in equity compared to childless employees, in data from 2020-2022. Mothers, however, earn equity at rates similar to non-parents. This data reflects those who hold roles at equity-granting companies, and does not capture the experience of those who may have left the workforce or shifted into roles that don’t grant equity after becoming a parent.

Hiring

Who’s being hired by startups?

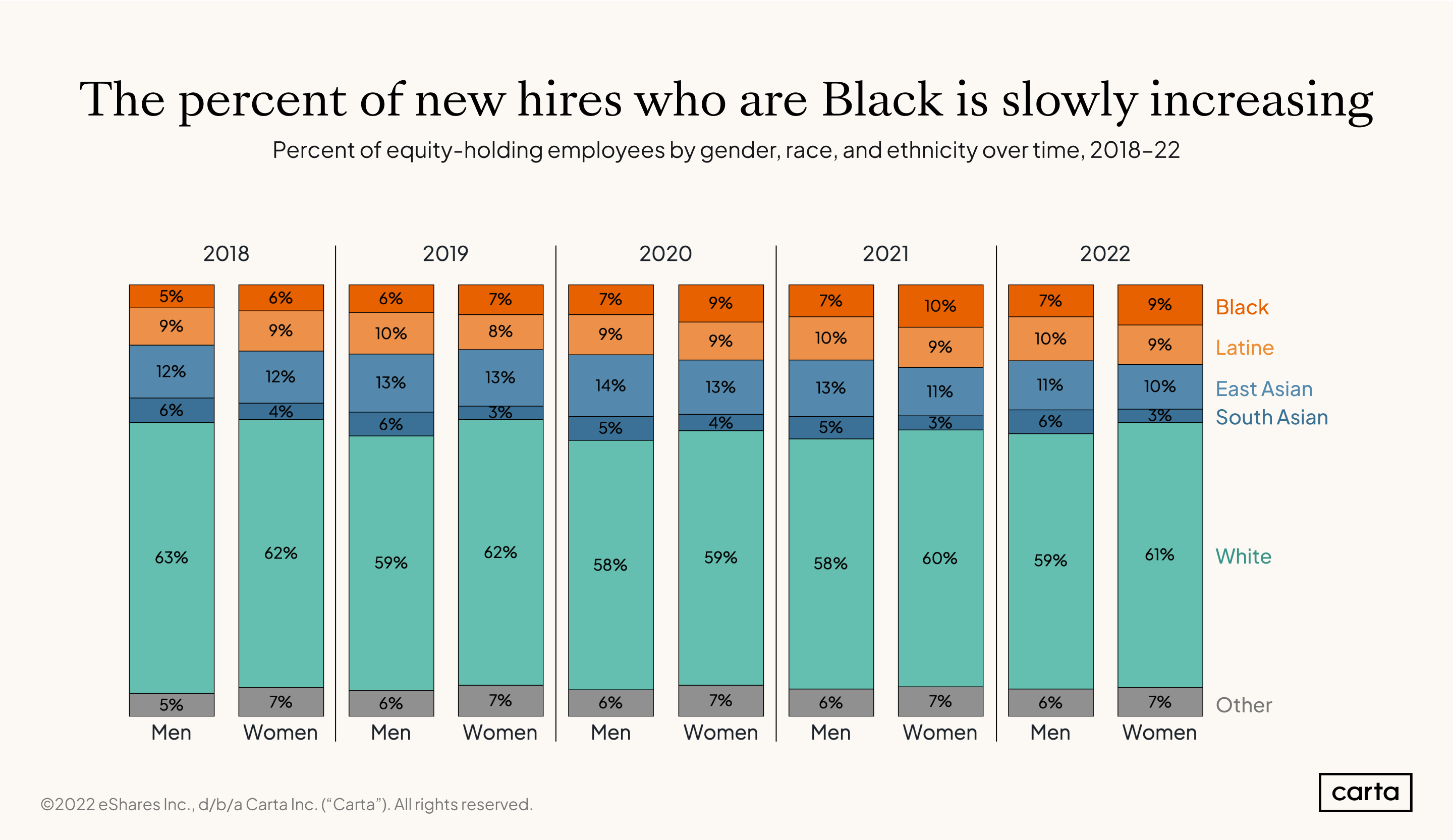

From 2018 to 2022, the percentage of new hires who are Black increased from 6% to 8%, with slightly more Black women than men hired. These numbers remain substantially less than the 12% that would be expected if hiring aligned with the overall U.S. labor force. The percentage of new hires who are white has stayed consistent over the past few years, tracking closely with the 61% of the overall labor force that is white.

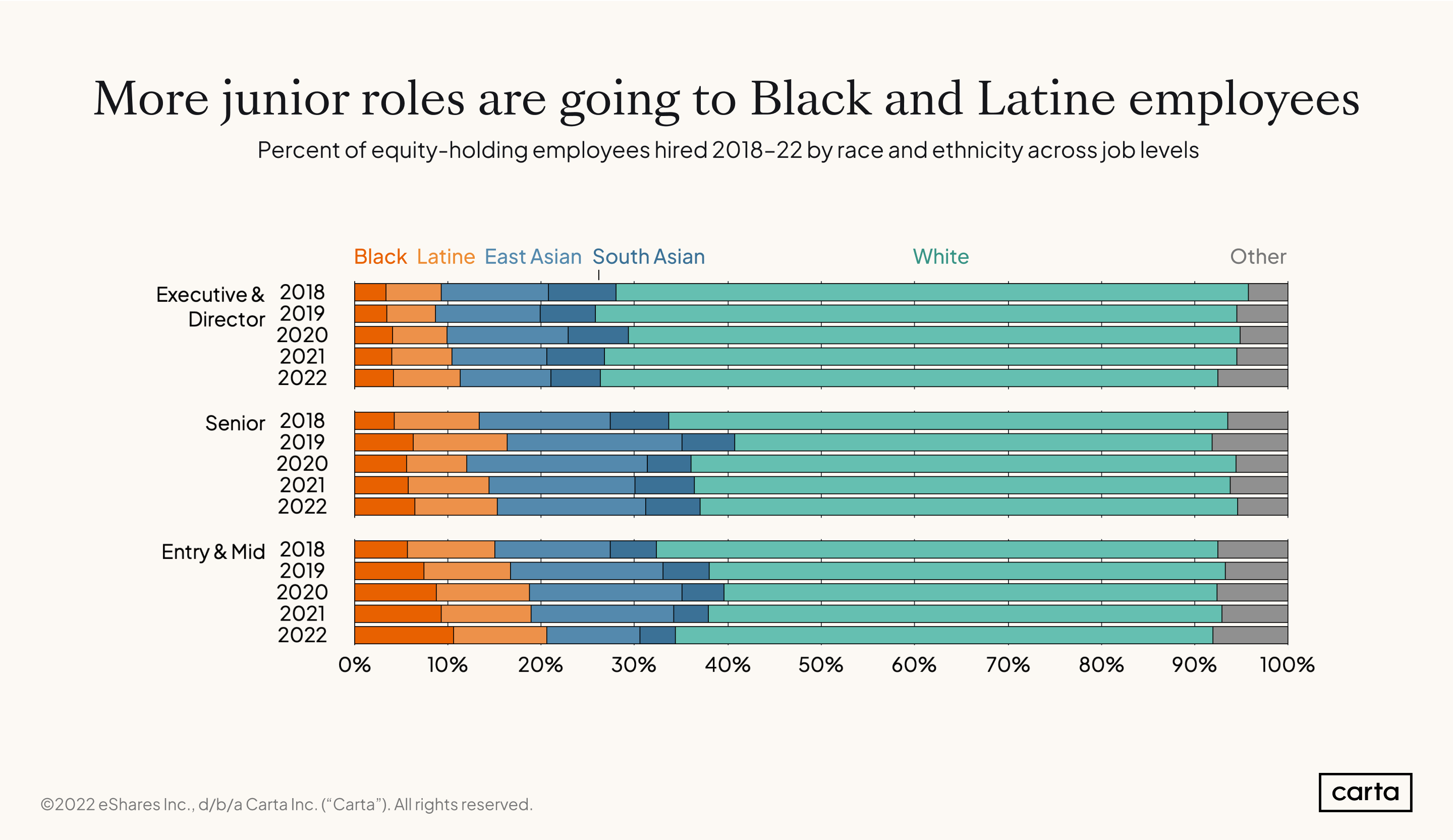

There has been more change over time in the racial makeup of new hires at the entry and mid levels, as compared with more senior levels. In 2018, 6% of employees at the entry and mid levels were Black. By 2022, this number was 11%. In contrast, at the executive and director levels, the percentage of employees that are Black went from 3% to 4%.

Latine employees have seen a smaller increase at the entry and mid levels, going from 9% in 2018 to 10% in 2022.

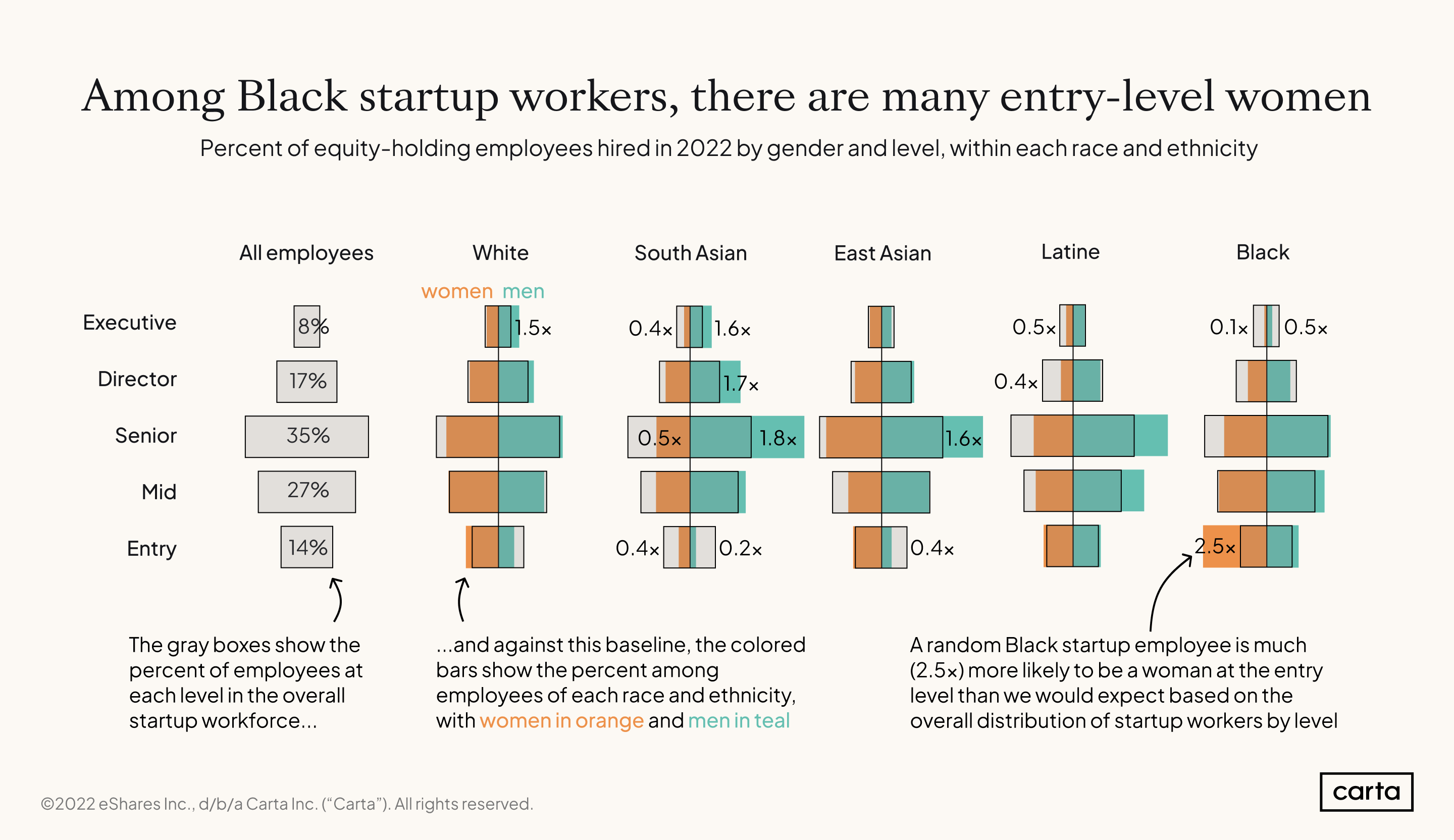

This chart looks at new hires by level in 2022. The rectangular outline is the overall distribution of hires by level—of all employees in the dataset hired this year, 14% were entry level, 27% were mid level, and so on. Only 8% of new hires were at the executive level.

However, if we look at startup workers of each race and ethnicity separately, this distribution by level looks quite different. Black men and women were both underrepresented at the executive level. While 18% of 2022 hires who are Black were women at the entry level, the percentage of women executives among hires who are Black rounds down to 0%.

The opposite trend is true for white and South Asian men. Both groups had a greater percentage of hires at the executive level than they did at the entry level. Among new hires in 2022 who are white, 6% are men at the executive level, and 5% are men at the entry level. Among new hires who are South Asian, 6% are men at the executive level and just 2% are men at the entry level.

This chart looks just at those within each race and ethnicity who are already startup employees, and the over- and under-representation of specific demographic groups relative to the U.S. labor force or overall population is in many cases even more pronounced.

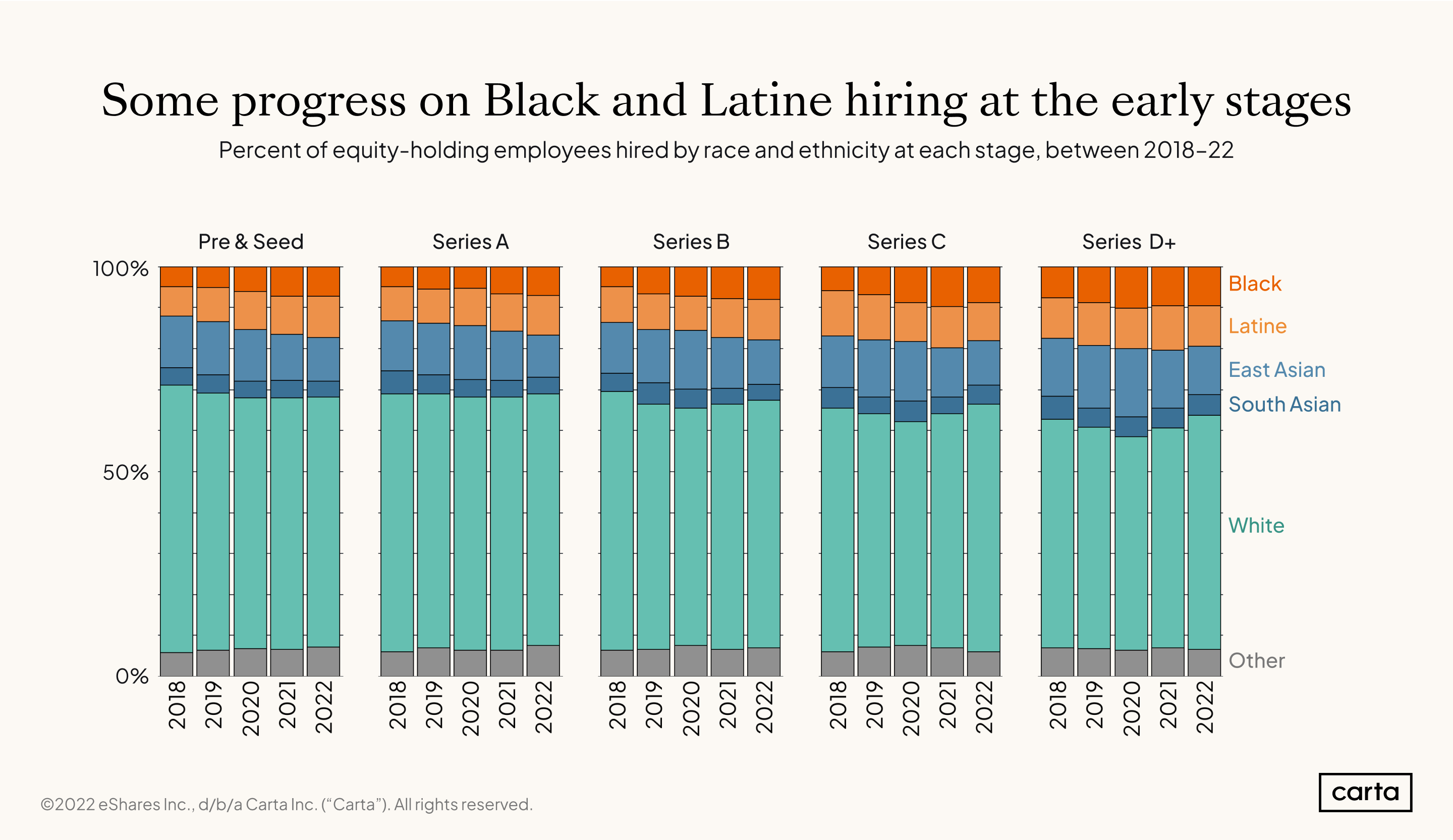

Over the past five years, early-stage companies have seen some movement in hiring Black and Latine employees—although, like companies at all stages, these groups are still underrepresented relative to their numbers in the U.S. labor force.

In 2018, 5% of new hires at pre-seed and seed-stage companies were Black and 7% were Latine. In 2022, those numbers were 7% and 10%, respectively. Black and Latine hires constituted 17% of hires at Series A companies and 18% of hires at Series B companies this year, compared to 13% and 14% in 2018.

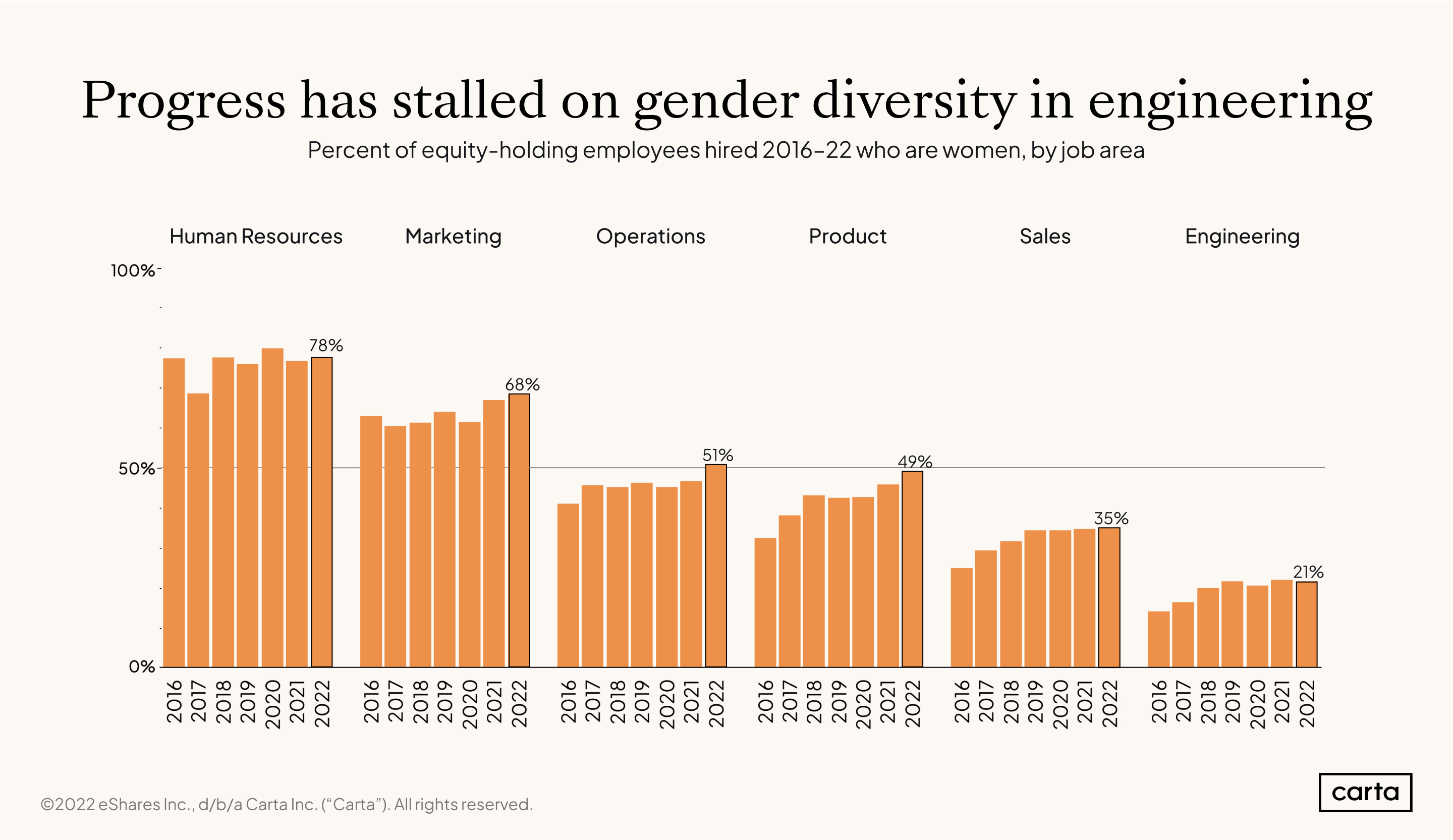

Between 2016 and 2019, there were slight improvements in gender parity in hiring in engineering, a field often dominated by men. However, hires of women have plateaued at about 20% for the last three years. The high point for hiring was in 2019, when women were 22% of engineering hires.

Human resources and marketing consistently hired more women than men from 2016 to 2022.

Marketing saw increasing representation for women over that time. In 2016, operations hires were 41% women; in 2022, women were 51% of hires. Product hires went from 32% women in 2016 to 49%, and sales went from 25% to 35%.

While the sample size isn’t large enough to report on representation of nonbinary people across all job areas, we did find that across all years taken together, sales has fewer nonbinary hires than other job areas.

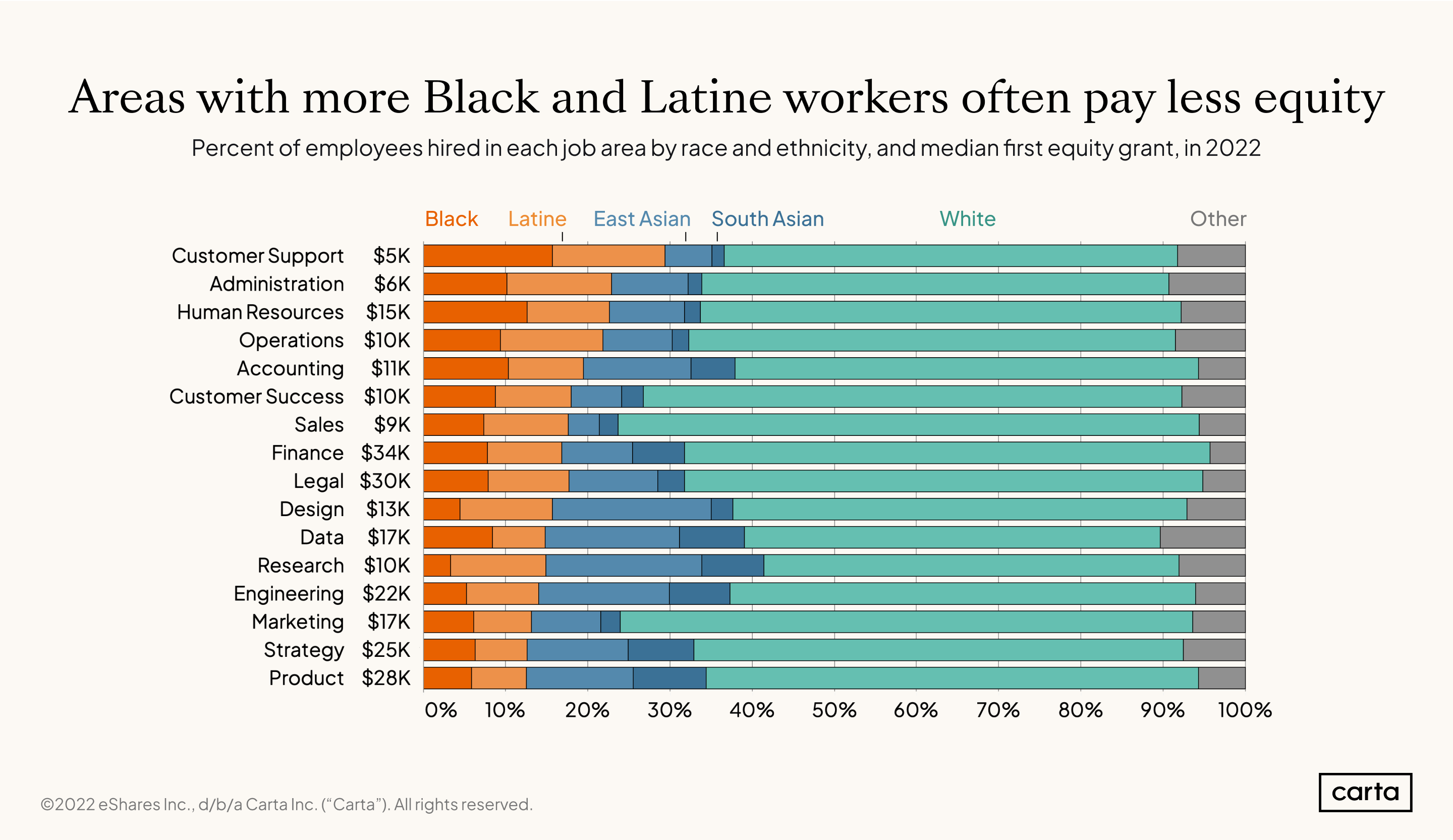

Job area is one factor in determining overall compensation, including equity grants. The median equity grant by job area varies widely, with the lowest for support roles and the highest for finance roles.

One factor contributing to this difference is the number of people at each level within each job area. People in customer support and administrative roles are often in more junior positions, compared to people in finance and legal roles. The median equity values here reflect the actual employee base in each job area, broken down by race and ethnicity.

There are more Black and Latine employees in administrative and customer support roles and more white employees in sales and marketing.

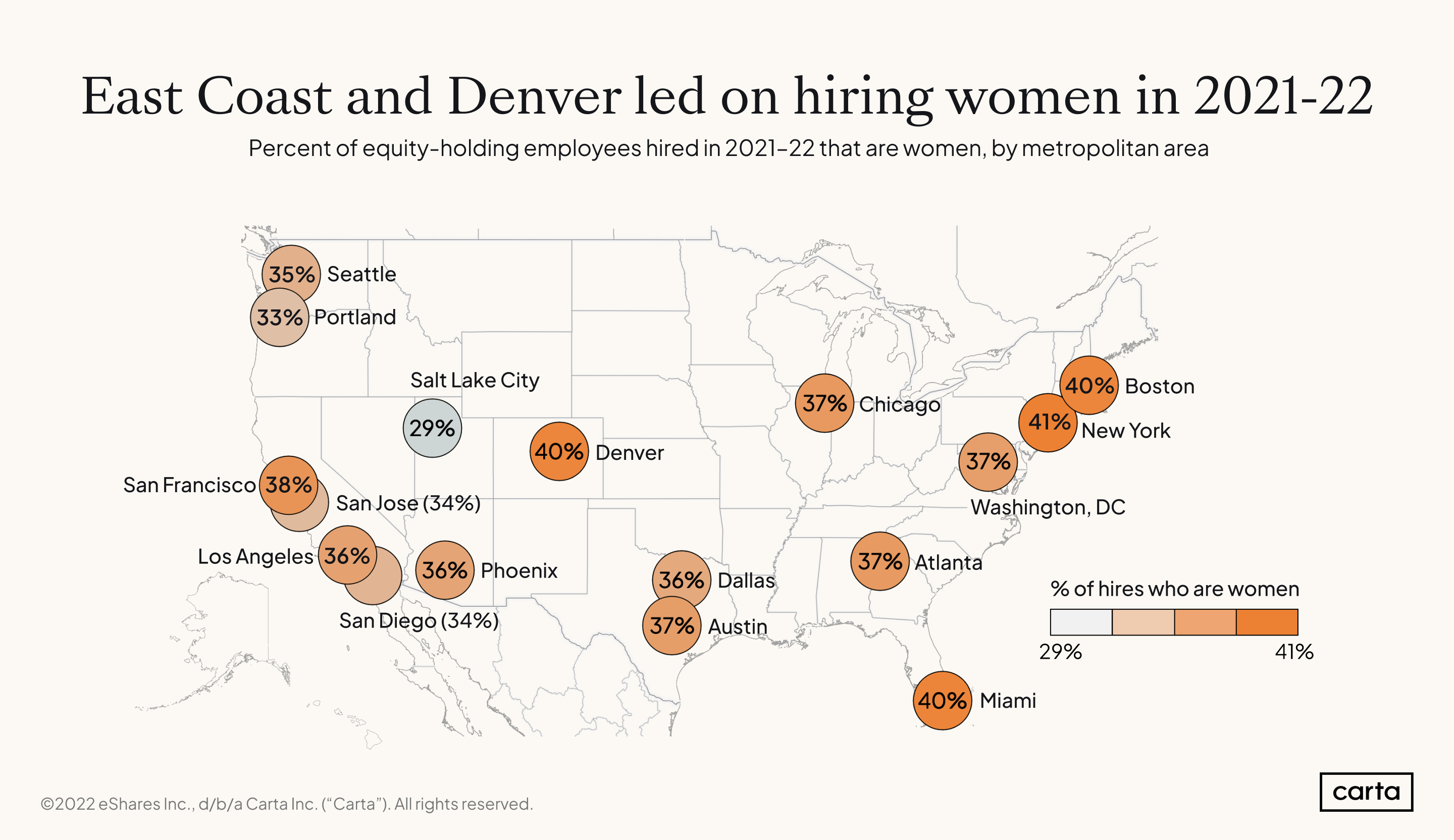

Where are startups hiring women?

Companies in Denver, as well as in East Coast metros including Miami, Boston, and New York hired women at higher rates than other metropolitan areas over the past two years. Companies in the New York metro had the highest rate of women hires—at 41%. This number is still below the 47% of the U.S labor force that are women. Salt Lake City-based companies hired women at a lower rate (29%) than companies in other metros in 2021 and 2022.

Equity in the C-Suite

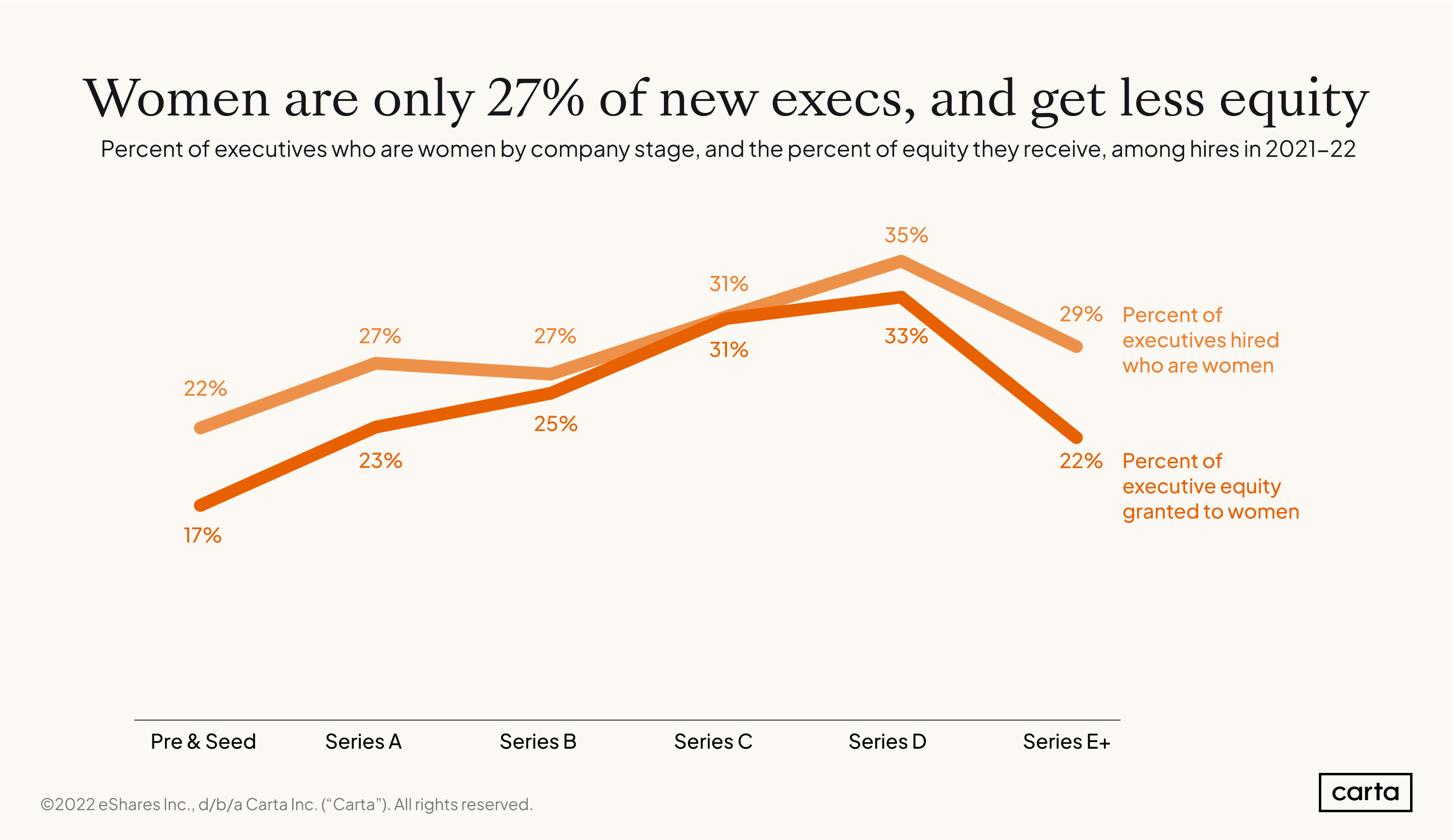

Looking at executives hired over the past two years, women are underrepresented at the executive level across all company stages; they also receive less equity than men in executive roles at the same stage of company. Only 27% of executive hires are women—and at the newest companies (pre-seed and seed stage), they’re only 22% of executive hires. The percentage of women in executive roles then rises, peaking at Series D.

The value of equity granted to executive women tracks even lower than the percentage of women hired into these roles—with the exception of Series C companies, where the percentages are in line. For reference, there is also a disparity among execs at public companies, where women execs own 1% of total shares in S&P 500 companies.

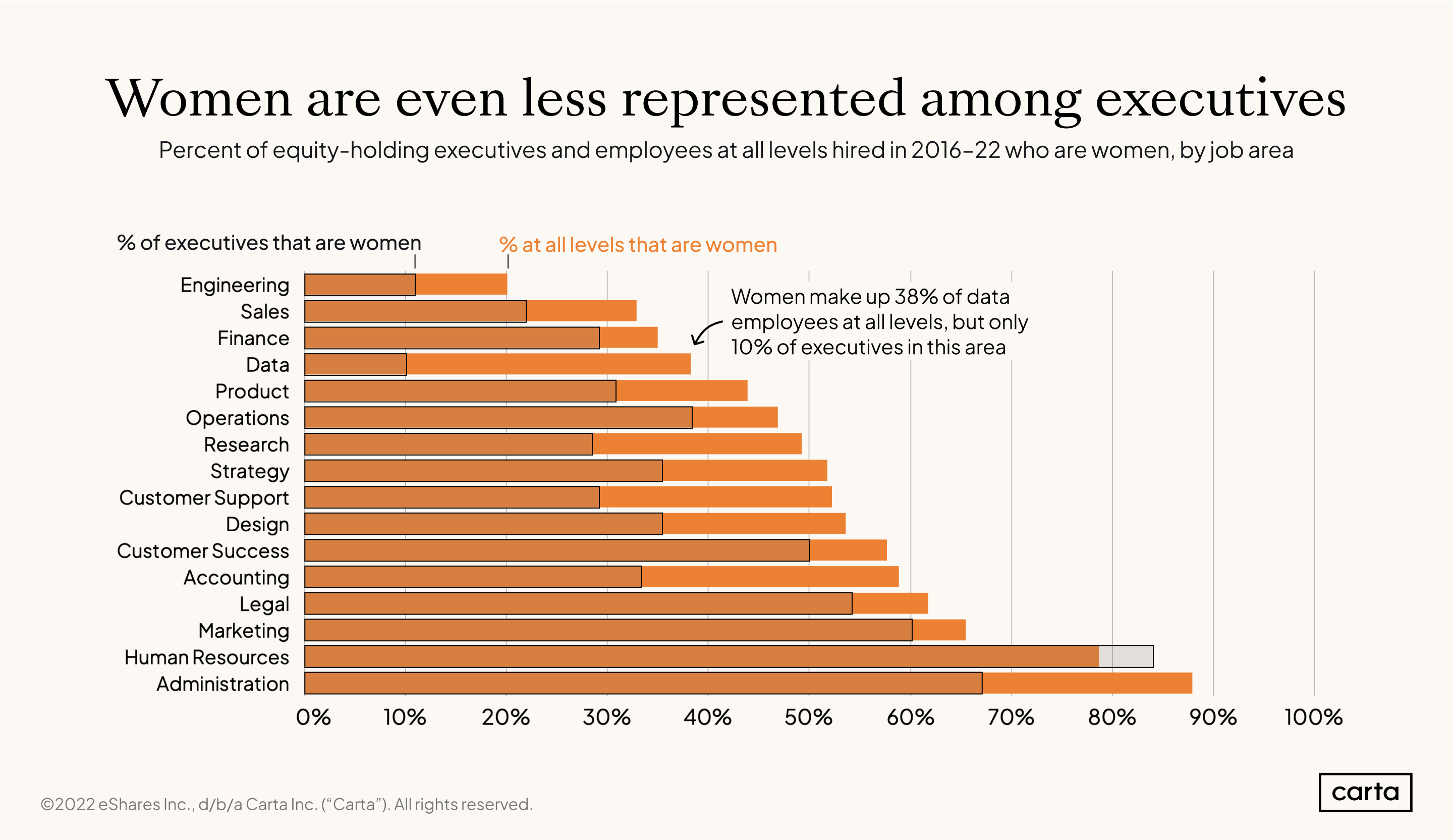

Men and women executives tend to be in different job areas, which is likely a factor in the disparities in equity. For example, 14% of women who are execs work in HR, and 22% are marketing leaders; only 2% and 12% of men execs are in these job areas, respectively. In contrast, 22% of men execs work in engineering, whereas only 5% of women execs do.

Job areas where women are underrepresented often have even fewer women than expected at the executive level. While 38% of data employees at all levels hired since 2016 are women, only 10% of new executive hires in this area are women. Similar trends showed up in other job areas dominated by men, as well as several areas where most employees are women. Only human resources had greater representation among women executives than among employees at all levels.

Legal, marketing, human resources, and administrative job areas all had more women than men executive hires from 2016 to 2022.

Employee option exercising

Employees who receive equity compensation in the form of stock options 5 must choose whether or not to exercise them, meaning to buy their stock at the strike price they were offered. There are many reasons an employee may choose not to exercise their options. Some employees may not have easy access to the cash they need to purchase options or the financial flexibility to have a significant portion of their net worth locked up in private market stock.

For this analysis, we looked only at the choice to exercise among employees whose options were “in the money”—that is, whose current 409A fair market value was higher than the strike price. But even with in-the-money options, employees may choose not to exercise because they don’t believe that the value of the stock will increase enough, or that an opportunity for liquidity will happen soon enough, to make the investment worthwhile.

Who exercises their options?

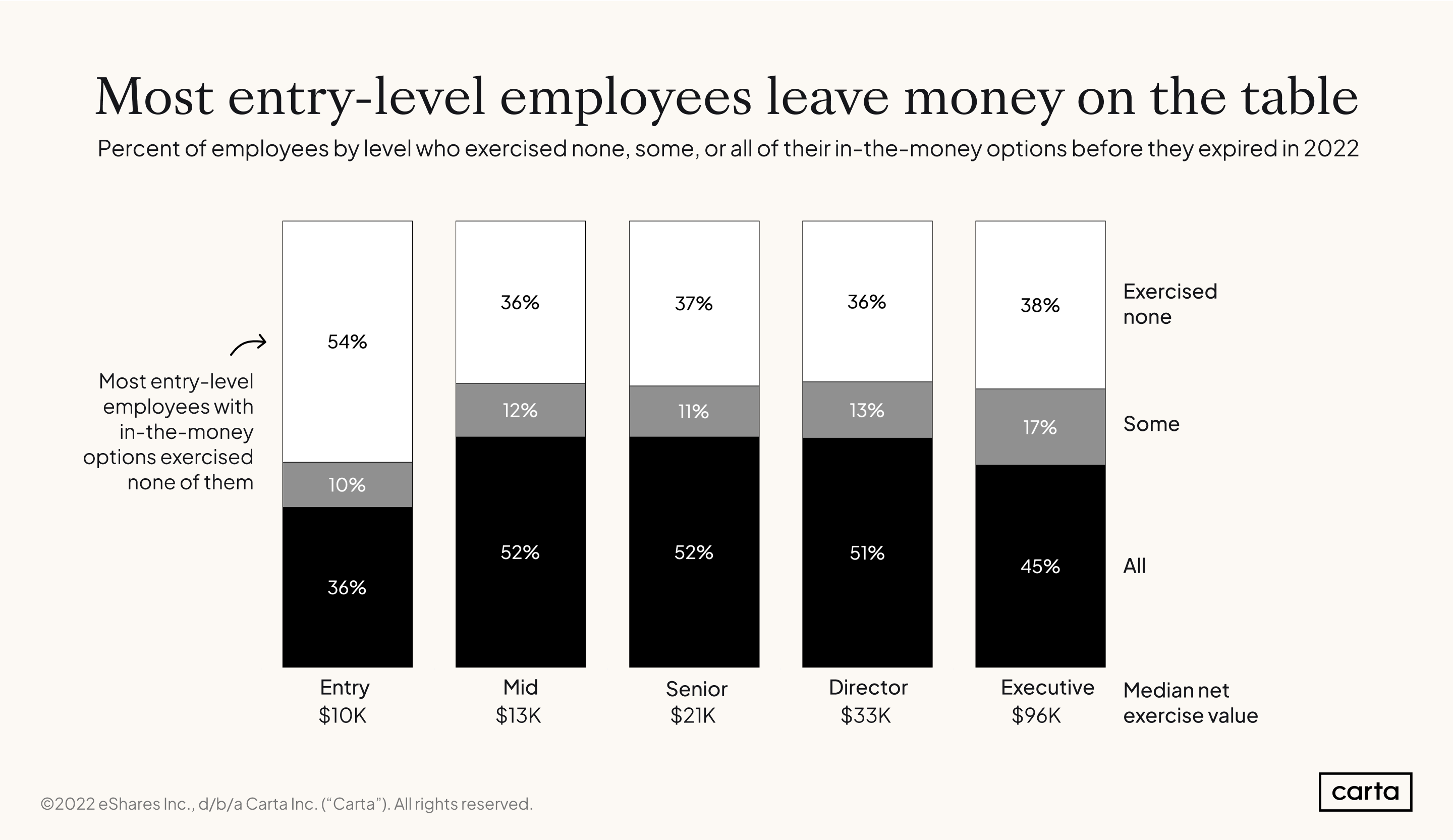

More than half of entry-level employees did not exercise any of their in-the-money options. Outside of the entry level, the majority of employees exercised at least some of their options.

There was a dip between directors and executives when it came to exercising all of their options, possibly due to the much larger size of grants to executives, making fully exercising more expensive.

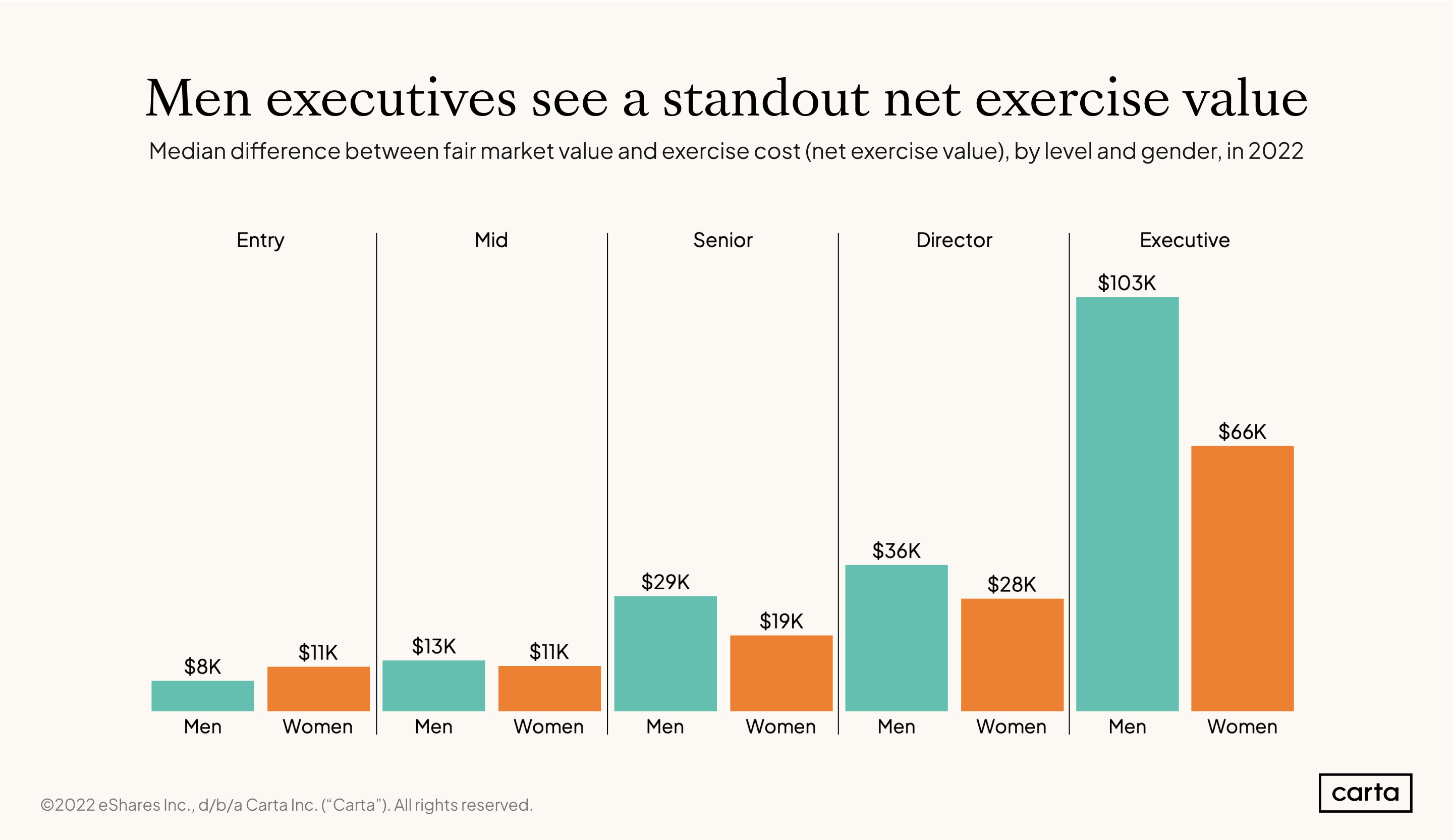

The median net exercise value—the difference between the fair market value and the strike price at time of exercise—for executives was $96,000. This paper gain was far greater than that of other groups (the median for one level down, director, was $33,000). The executive level also did more partial exercising than any other group.

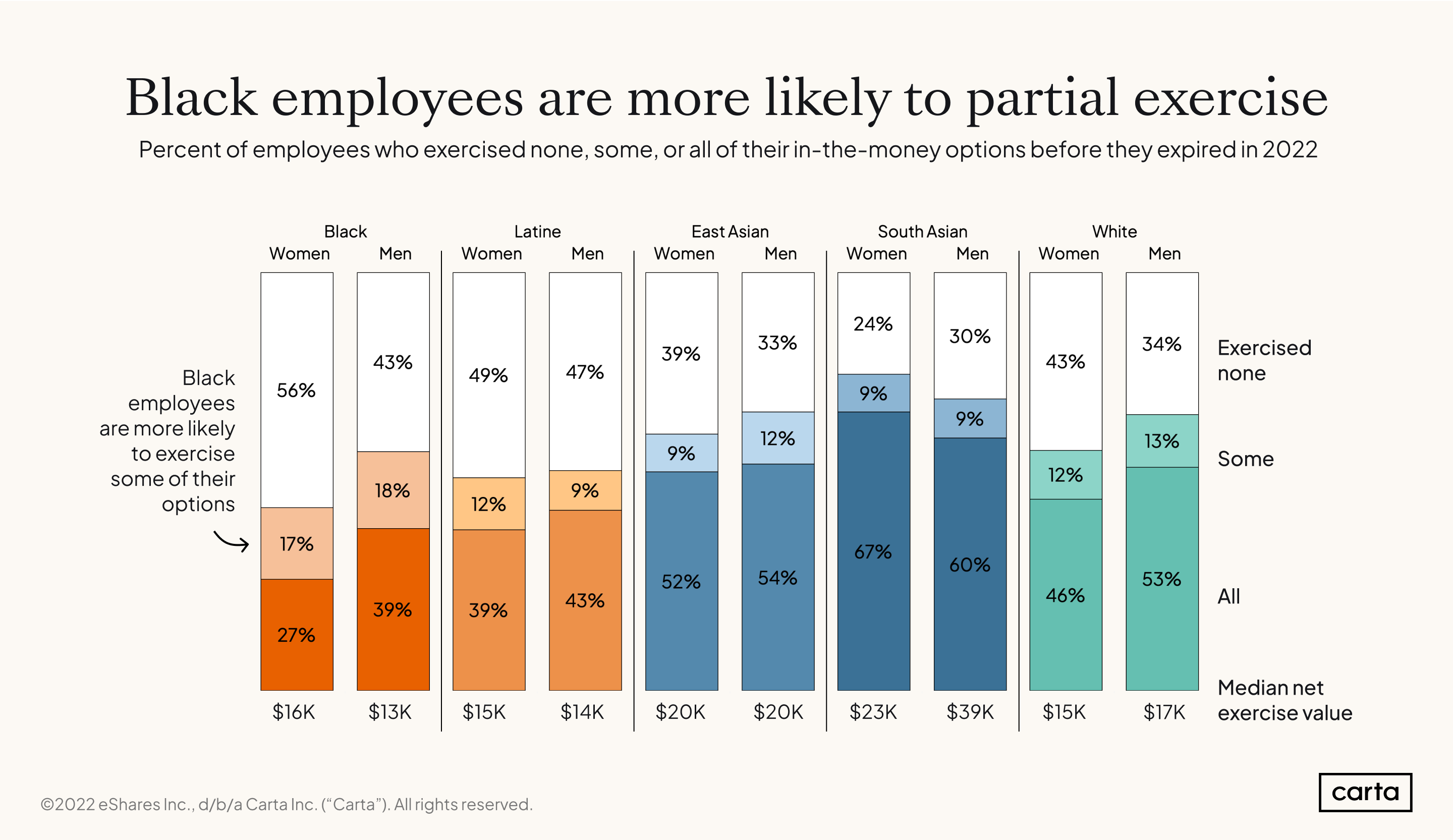

Across most race and ethnicity groups, men exercised their in-the-money options more than their women counterparts did. Overall, 45% of women who shared their gender with us fully exercised their in-the-money options, compared to 52% of men. (Note that exercise rates are somewhat higher among people who have completed their demographic profiles on Carta; overall, including people who have not shared demographic information with us, 46% exercised all of their in-the-money options.)

South Asian women exercised all of their options more than any other group (67%); they were also the only group of women who fully exercised at a higher rate than their men counterparts did. Black women were the least likely (27%) to exercise all of their options. However, Black men and Black women were the two groups who most often “partial exercised,” or bought some—but not all—of their options.

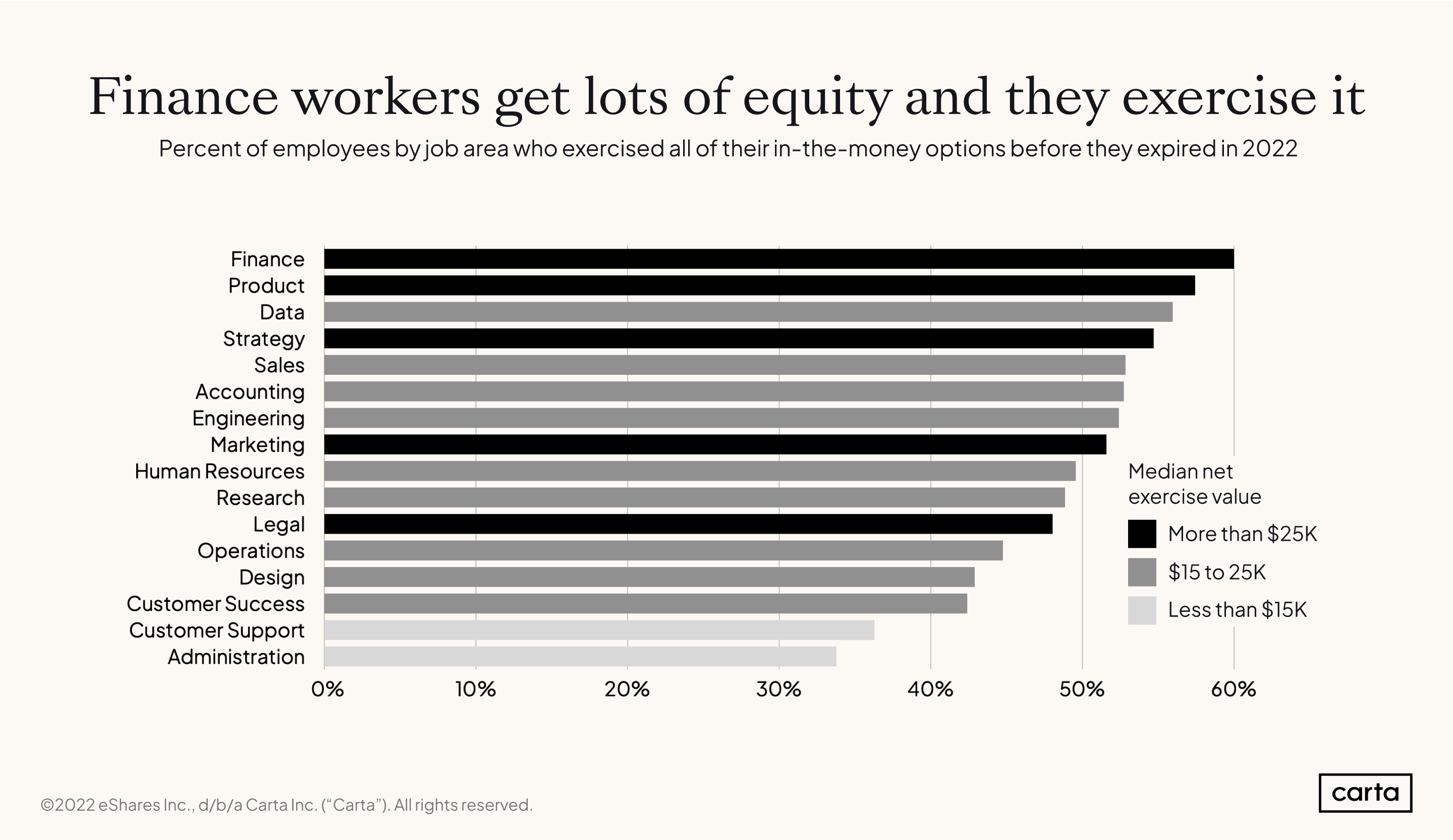

Employees in finance were most likely to exercise all of their stock options. Those in administrative and customer support and success positions were least likely to do so.

This pattern tracks with differences in compensation between job areas; lack of resources might be a reason why employees in those roles don’t exercise as much. Employees who work in finance specifically may also have more knowledge about stock options and financial planning, which may make them more likely to exercise their in-the-money options.

Where are people exercising their options?

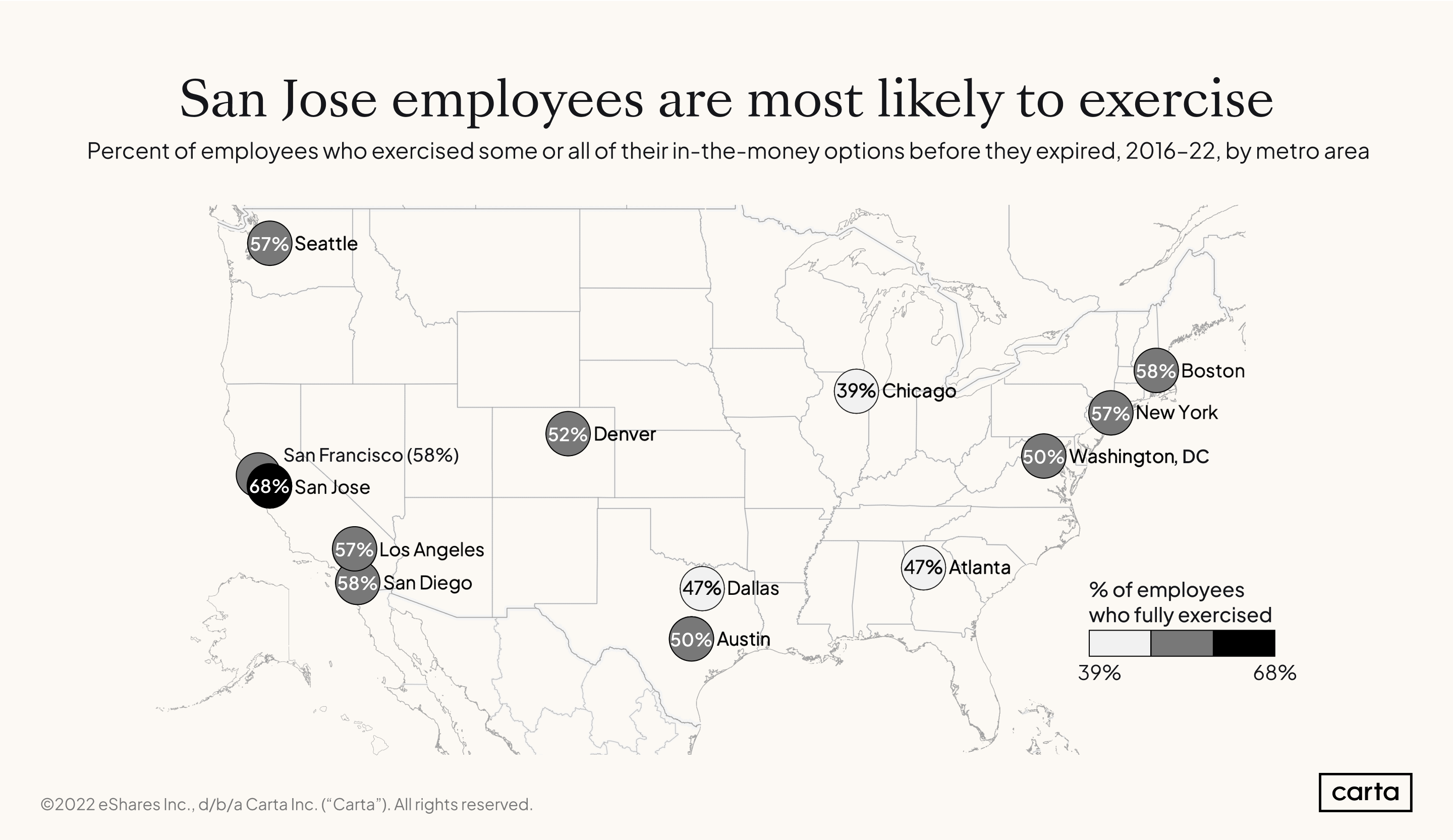

San Jose is an outlier: 68% of employees exercised at least some of their in-the-money options that had expiry dates within the last five years. San Francisco and Boston came next, followed by New York, Los Angeles, and Seattle. On the low side: Chicago, where only 39% of employees exercised some or all of their in-the-money options before they expired.

The median paper gain on exercise (or net exercise value) by metro area did not follow these same patterns; employees in Chicago and Denver saw the highest median paper gain on exercise during this time period, albeit for a smaller total number of employees.

Who profits from equity exercise?

In 2022, men who are executives had the highest paper gain at the time of exercise. Both men and women executives saw more than double the paper gain, compared to their counterparts at lower levels.

At almost every level, men saw a larger paper gain than women did. The one exception was entry level, where women saw a median of $11,000 while for men, it was $8,000.

Founders

Race and ethnicity

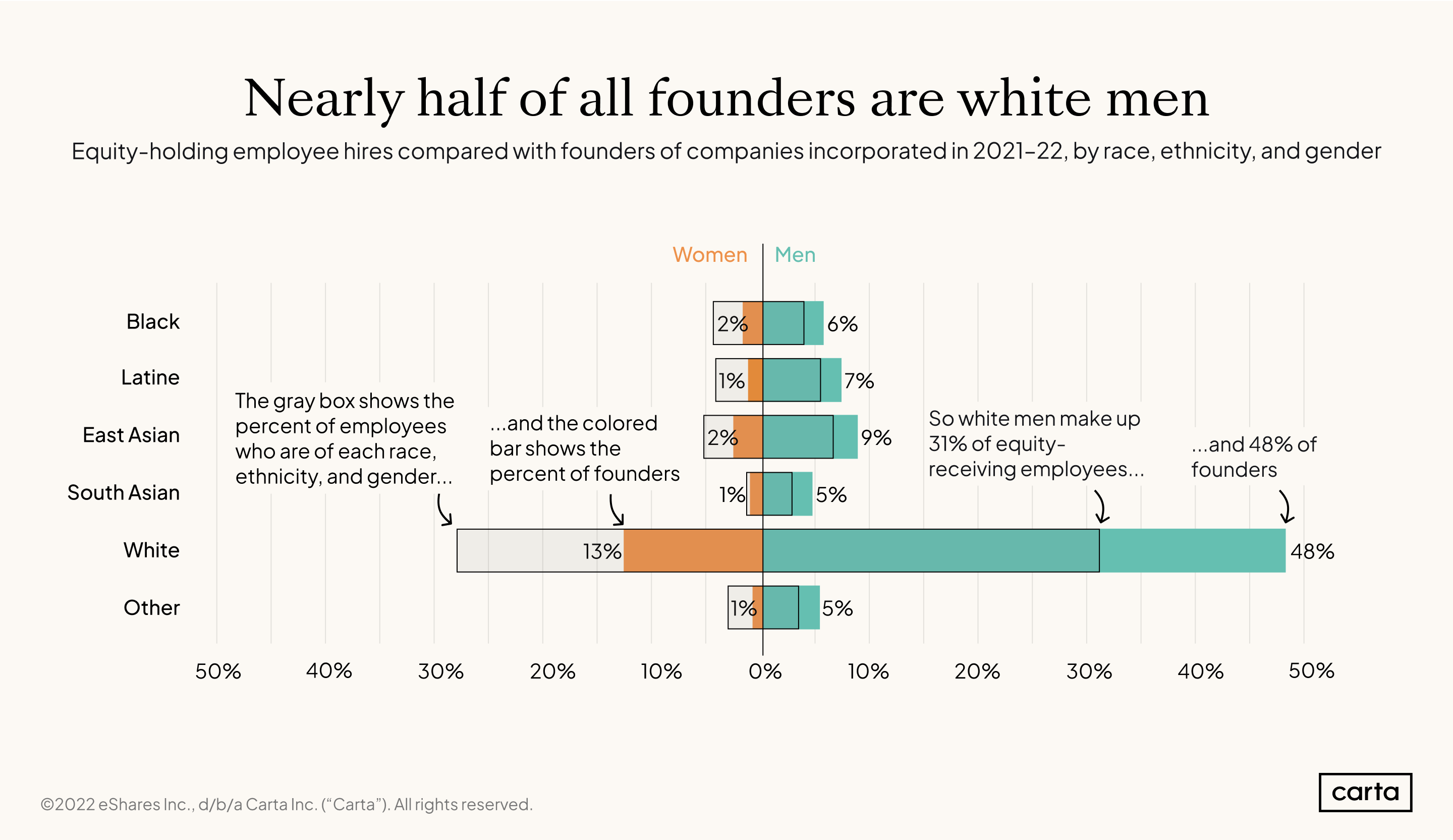

White men founded nearly half (48%) of all companies incorporated in 2021 and 2022. The gender imbalance in founders of all races and ethnicities (represented by the colored bars) was greater than it was for employees hired in this timeframe (represented by the box outline).

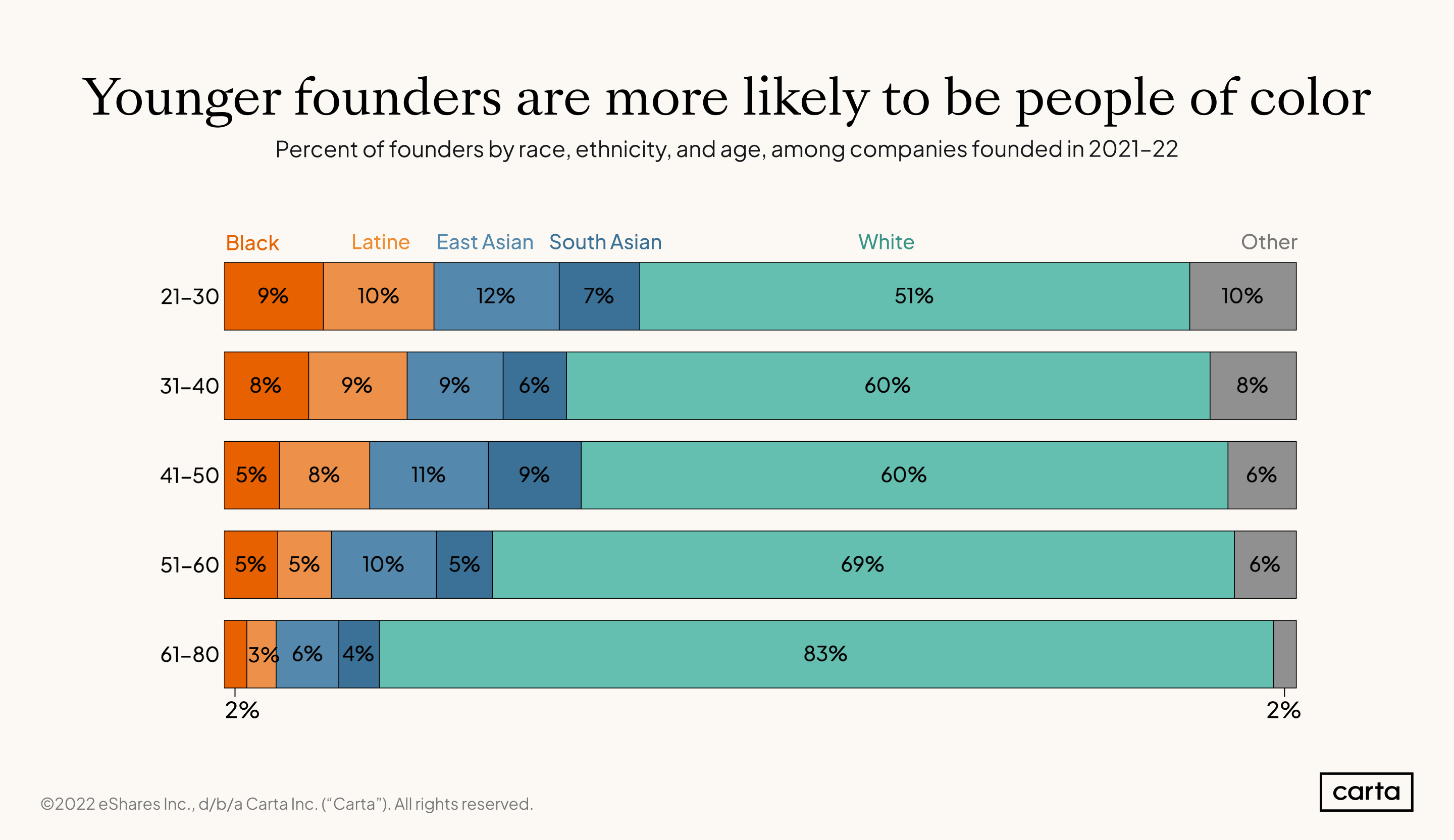

There are more founders who are Black, Latine, East Asian, South Asian, and “Other” in younger populations. The percentage of white founders rises from just over half of those in their 20s to over three-fourths of those in their 60s and 70s.

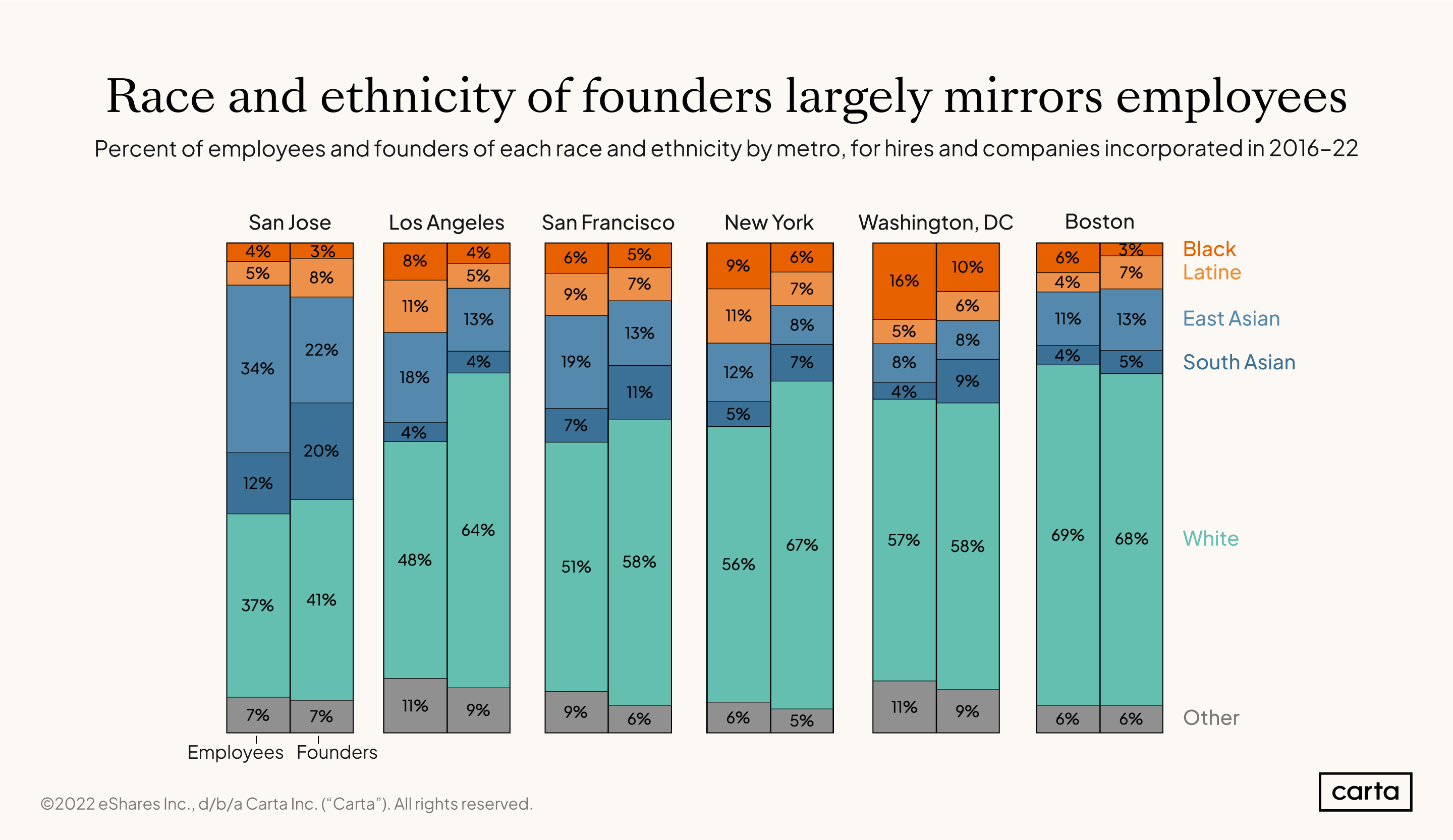

There’s a gap between founders and equity-receiving employees by race and ethnicity in some metro areas. In Boston, 6% of employees hired in 2016-22 were Black, compared to 3% of founders of companies incorporated in this same timeframe. In Los Angeles, 11% of employees were Latine and 8% were Black, compared with 5% and 4% for founders, respectively.In Washington, DC, 4% of employees were South Asian, compared with 9% of founders.

Gender

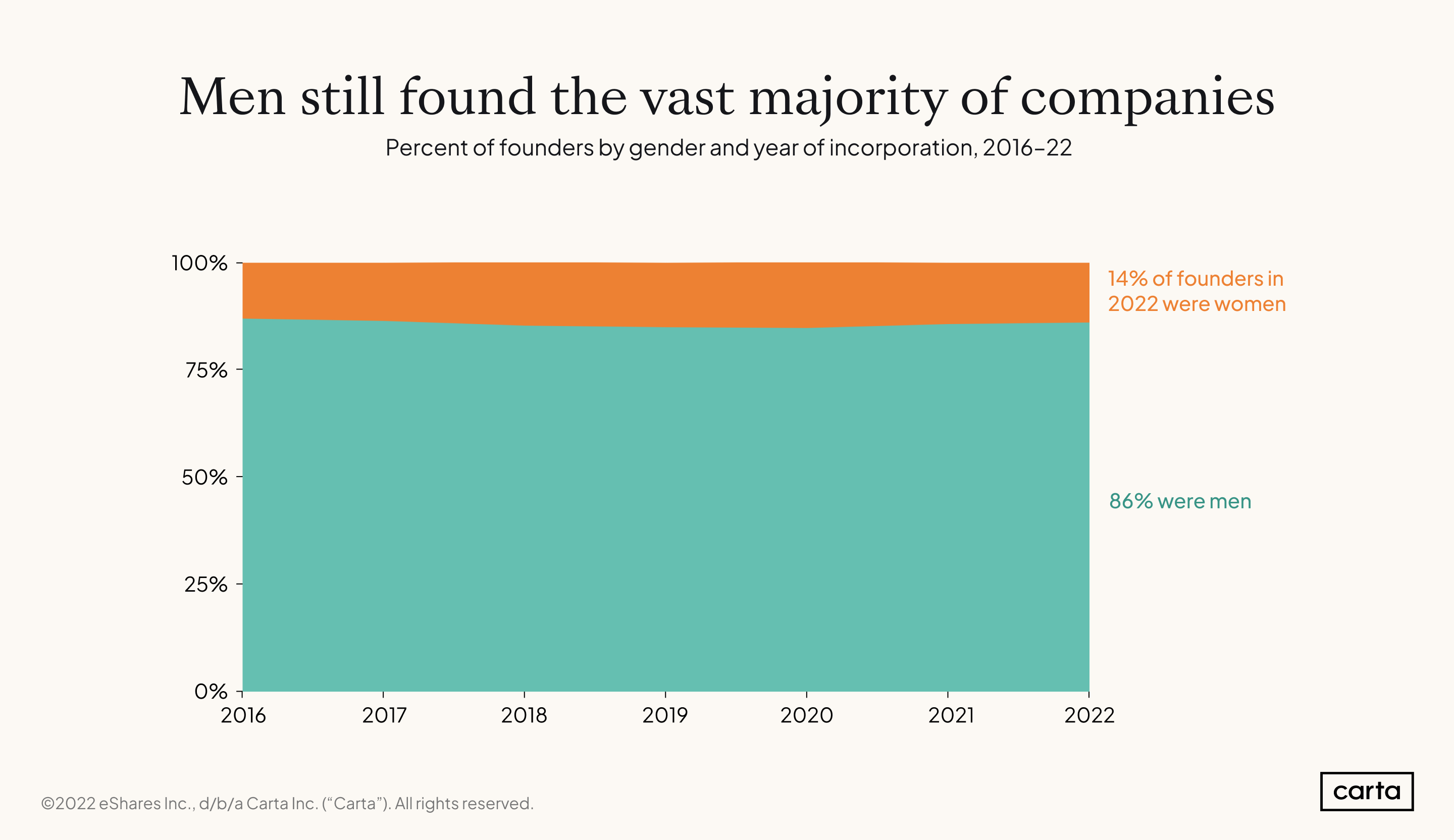

The large majority of founders are still men. In the last six years, there has been little change in the percentage of founders who are women, ranging from 13% in 2016 and 2017 to 15% between 2018 and 2020. Men made up 86% of founders who incorporated their companies in 2022.

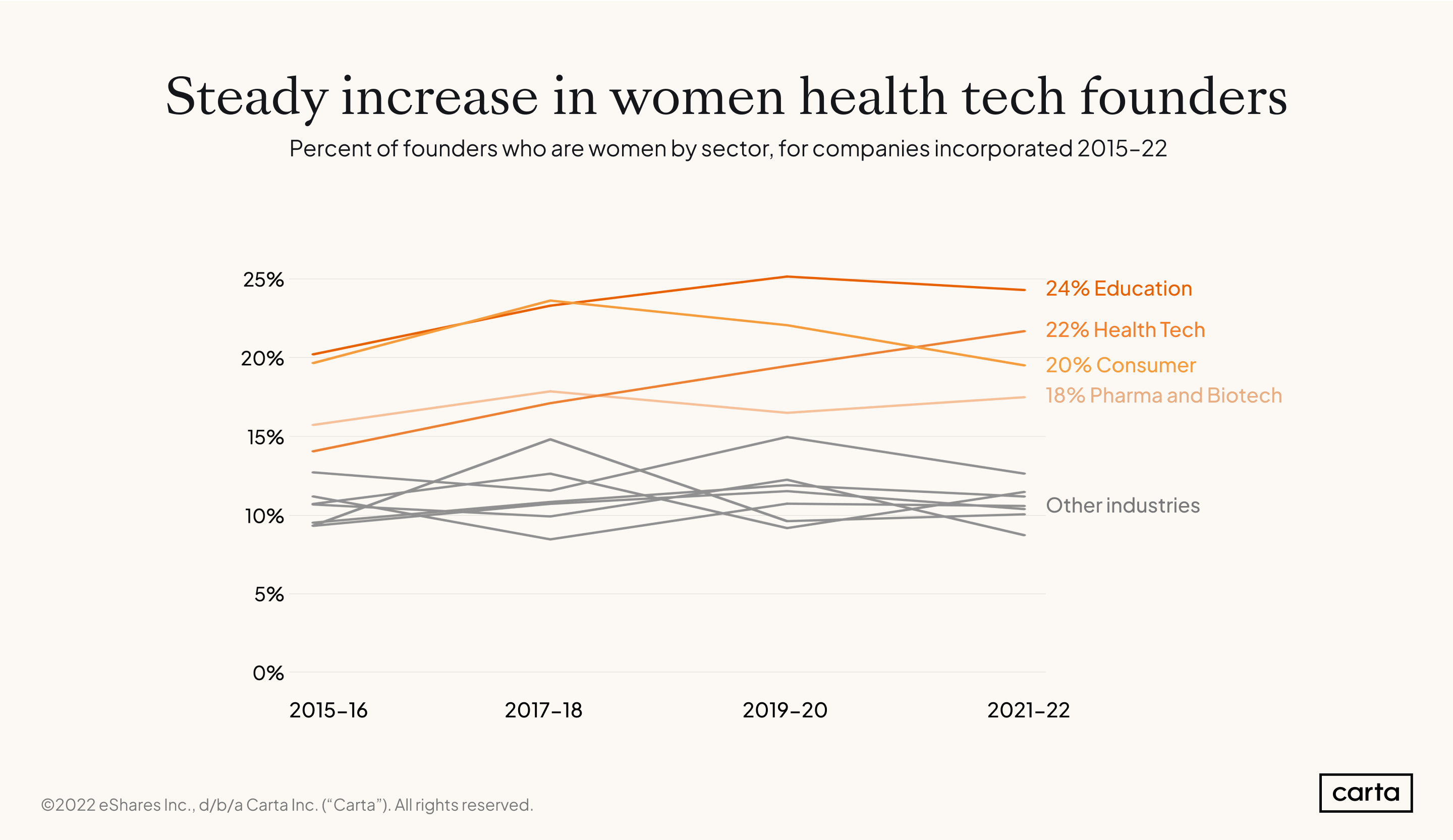

The gender balance of founders varies by industry. The most women founders are in education and health tech; the fewest are in the gaming industry. Even in the most-represented industries, the percentage of women founders was still under 25% in 2022.

Gender and co-founding teams

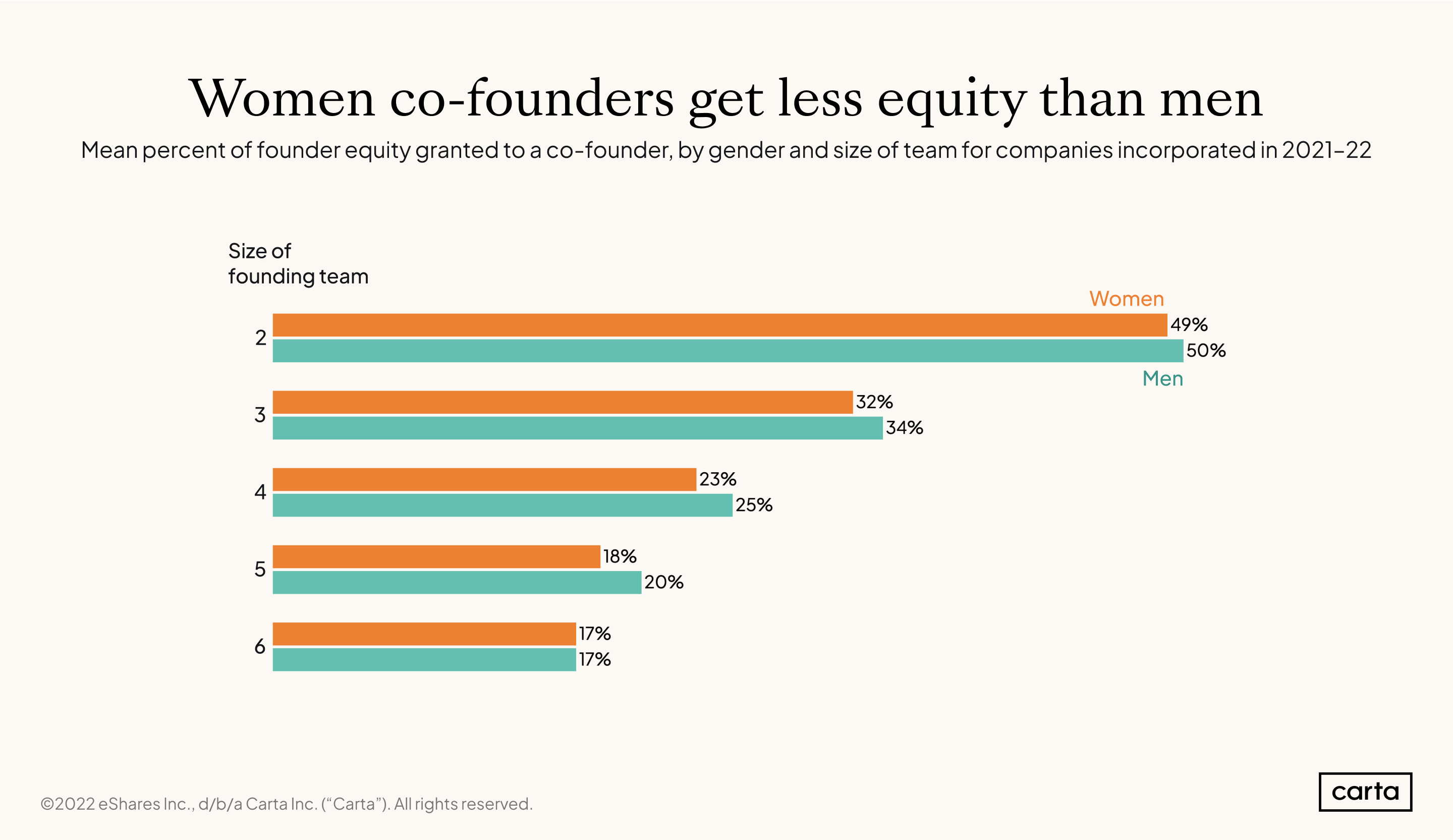

When there’s a solo founder, the equity split is simple: That founder gets 100% of all founder equity. With more co-founders, the split isn’t always equal. It can be impacted by factors such as job area, experience, and time spent at the company—as well as bias and differences in negotiation style.

For founding teams of almost all sizes, women tend to receive less equity than men. This only evens out in cases of six co-founders.

Women on founder teams of two pull in an average of 49.2% of founder equity, versus an average of 50.1% for men who have one co-founder. (Note that these percentages do not sum to 100% because there are more men than women founders.)

Differences between co-founders are largest on teams of five, where women get an average 18.0% of founder equity, while men get an average of 20.3%.

Three is the most common number of co-founders for a company to have, so we looked at the gender composition of three-person teams. Among three-person teams, 70% are three men; 24% are two men and a woman; 4% are two women and a man; and 1.4% are three women.

Another way to put this is that if you’re a woman founder with two co-founders, there’s a 79% chance that you’re the only woman on the team. But if you’re a man founder with two co-founders, there’s a 5% chance that you’re the only guy.

Investors

We analyzed venture capital investment by looking at general partners (GPs)—who run venture capital funds and decide which companies to invest in—and limited partners (LPs) who contribute money to VC funds. GPs often invest their own money in the fund as well as deploying the investments of LPs.

LPs can be individual people or other entities, such as trusts, LLCs, corporation, and retirement funds. When looking at demographic information like race and gender, we narrowed our focus to limited partners who are individual people, rather than multiple people (such as a family) or any other entity type. For geographic patterns, we looked at the mailing address of GPs and LPs, including both individuals and other entities.

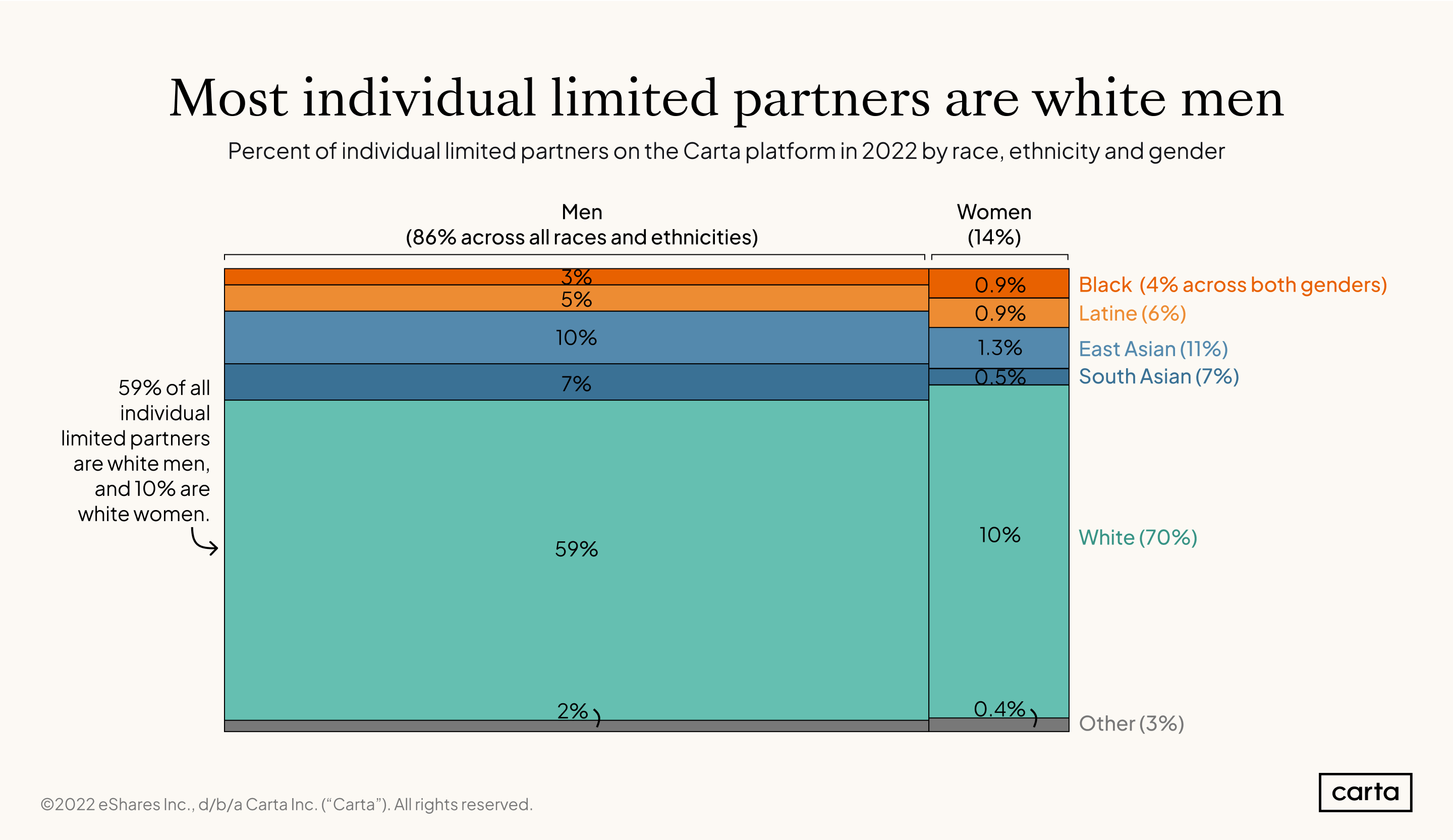

The majority of individual limited partners are white men. Overall, 86% of LPs are men and 14% of LPs are women. Seventy percent of LPs are white.

Although there are far fewer women LPs in general, they’re slightly more likely to be white, Black, or Latine than their counterparts who are men—and less likely to be East or South Asian.

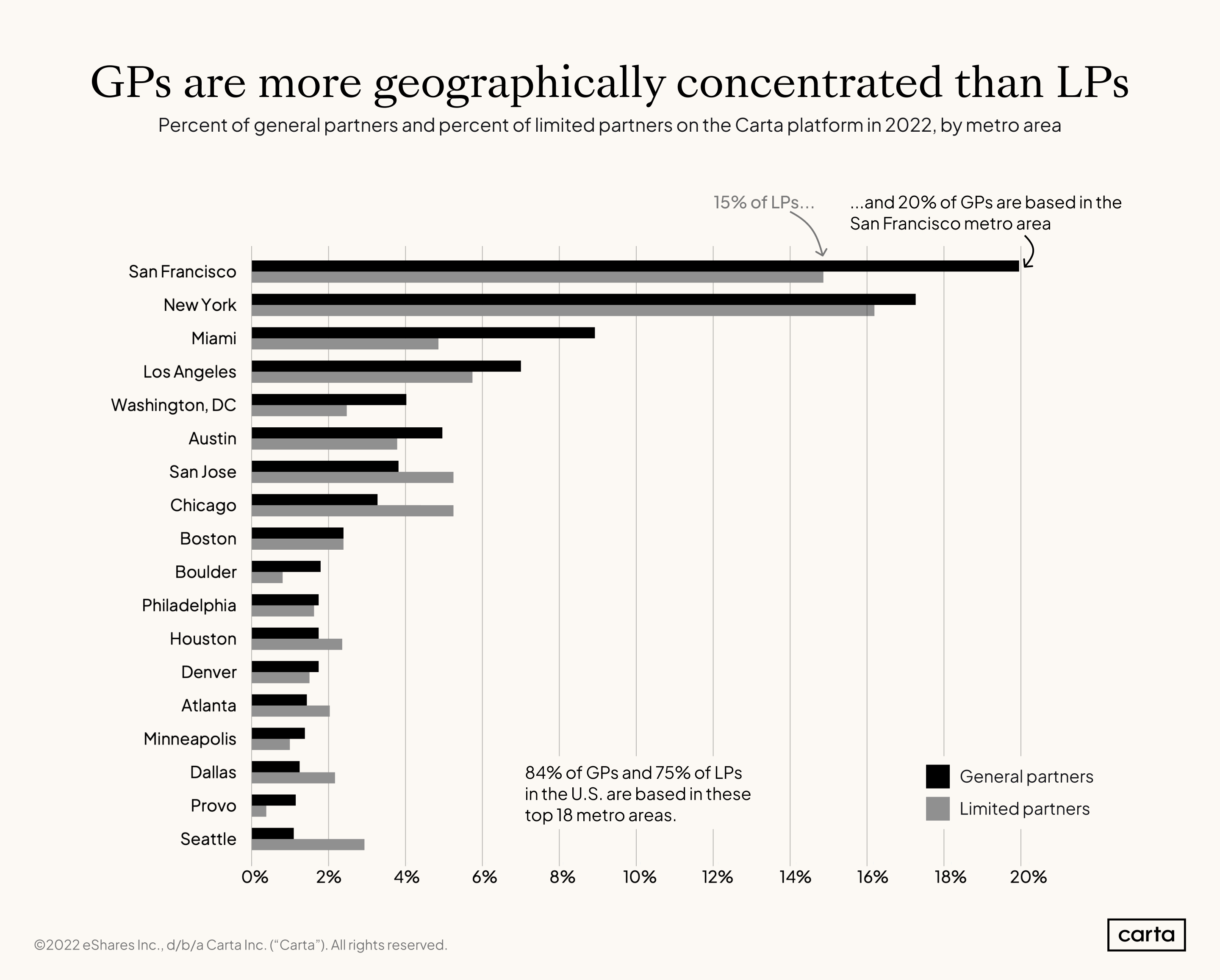

Investors are largely concentrated in major metro areas. About one-third of all investors (37% of GPs and 30% of LPs) are in either New York or San Francisco.

GPs are more concentrated into these metros than LPs are. This may be because limited partners’ involvement in funds consists mainly of contributing capital, which can be done from anywhere, while being a general partner involves more networking and may benefit from being closer to startup hubs.

Women LPs invested in smaller funds than men in 2021–22. 6 On the lower end of investment, men and women invested similarly: The 25th percentile of fund size was similar, at $8 million for women and $9 million for men. The 50th and 75th percentiles differed more. The median fund size that women invest in was $15 million, compared to $22 million for men. The 75th percentile for investment by women was $35 million; it was $48 million for men.

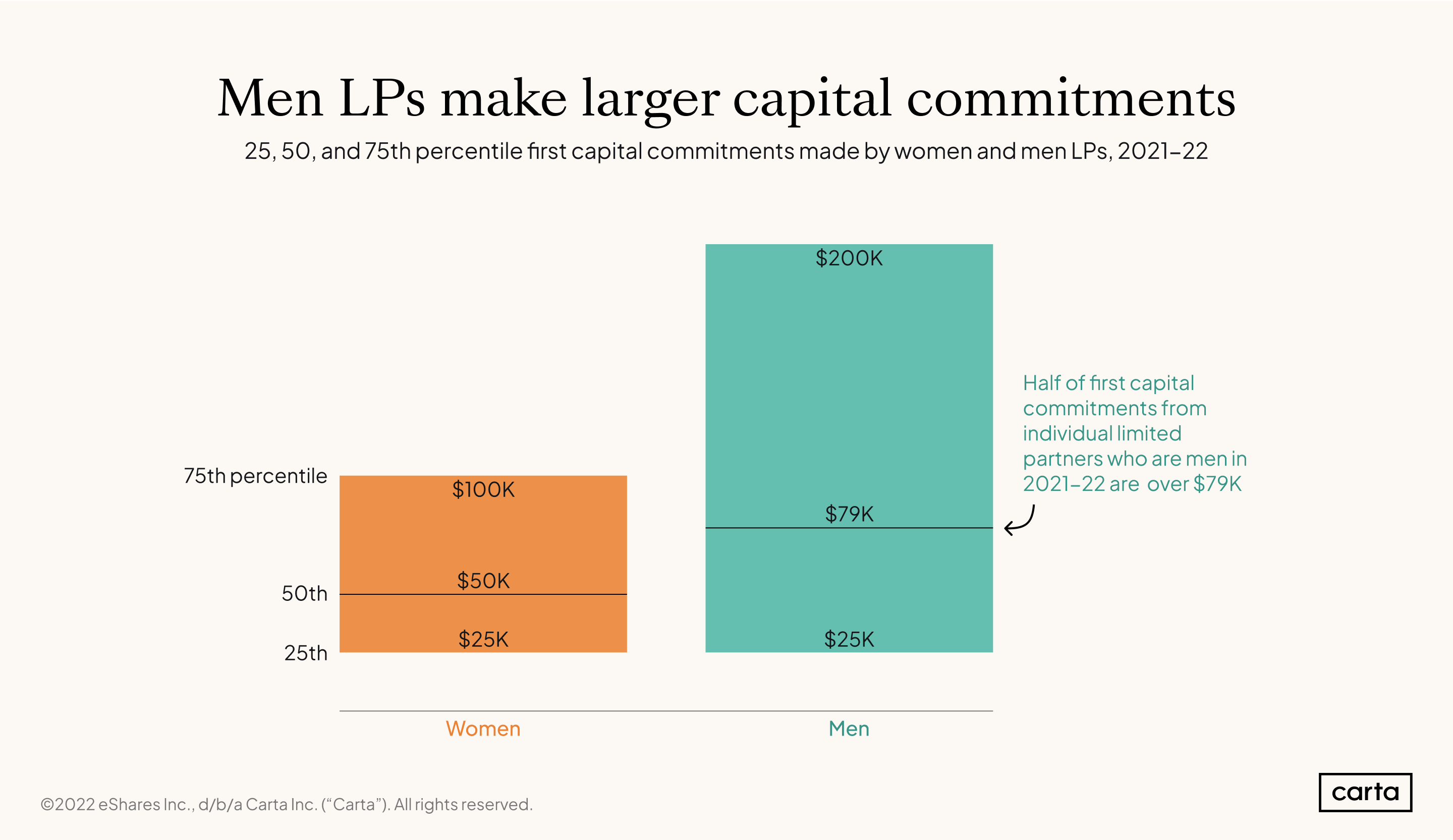

When it came to the size of the first checks that women LPs wrote into funds on Carta in 2021–22, a similar pattern emerged. Again, the lower end of this chart is more consistent, with the 25th percentile coming in at $25,000 for both men and women. But the median LP who is a man 7 committed considerably more than the median woman LP, and the 75th percentile was twice as much for men as for women.

LLCs

Throughout this report, our data is focused on traditional corporations, which form over 90% of the customers of Carta’s cap table product. But limited liability corporations (LLCs) are also able to issue equity to their employees—and a growing number of them are doing so on Carta. Eight percent of Carta’s current cap table customers are LLCs.

LLCs are formed for a number of reasons. Unlike traditional corporations, which are structured in a way that makes it possible to go public one day, LLCs may have different goals. Some may transition to a corporate structure down the line; others may choose an LLC structure indefinitely and still create ownership through equity. We look forward to diving more deeply into LLC equity patterns in coming years.

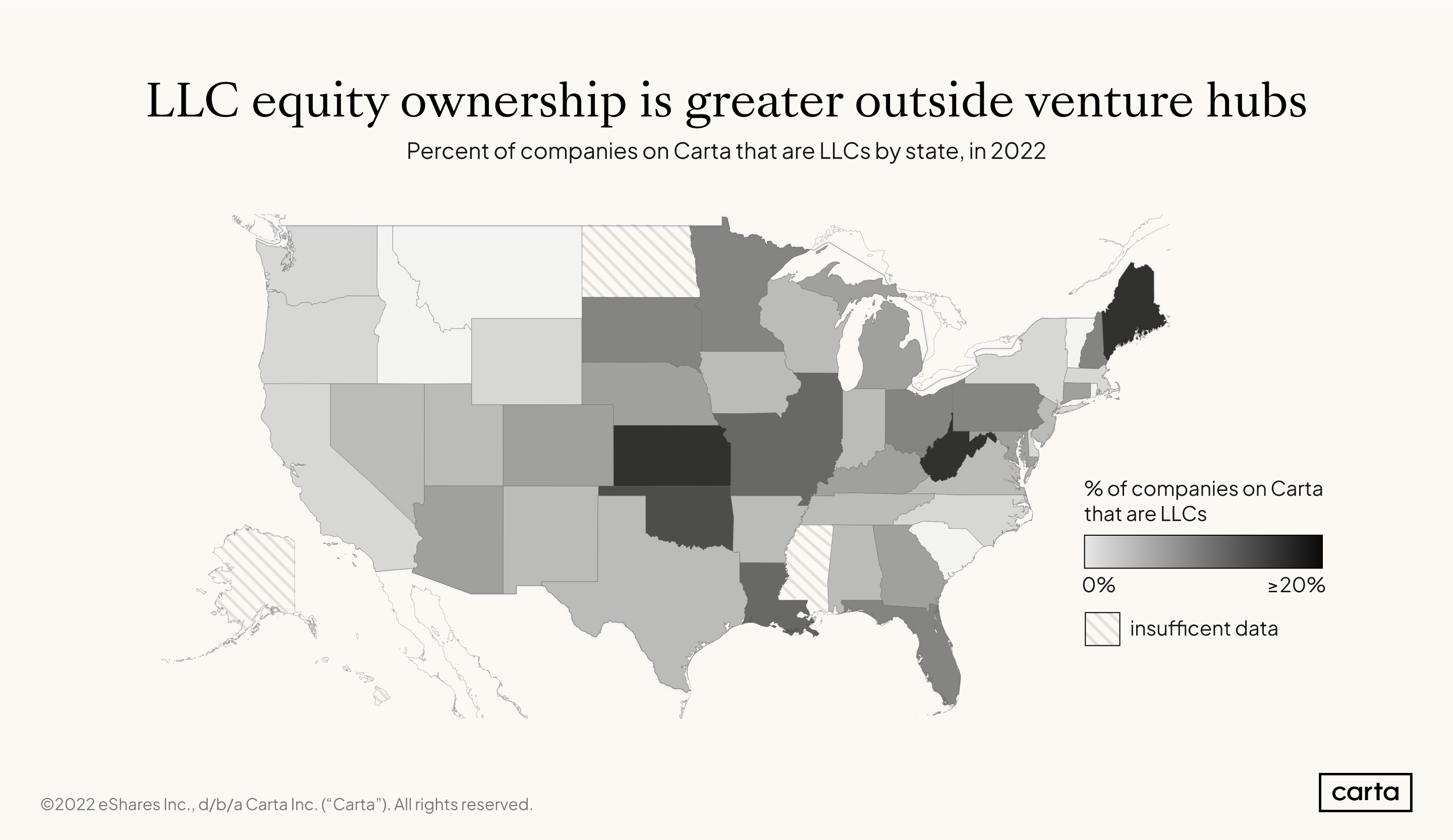

States outside the major venture hubs had a higher concentration of LLCs. In Kansas, West Virginia, and Maine, more than 20% of companies on Carta are LLCs (out of a total of 90 companies). In contrast, 3% of the over 10,000 companies in California and 5% of New York’s over 3,000 companies are LLCs.

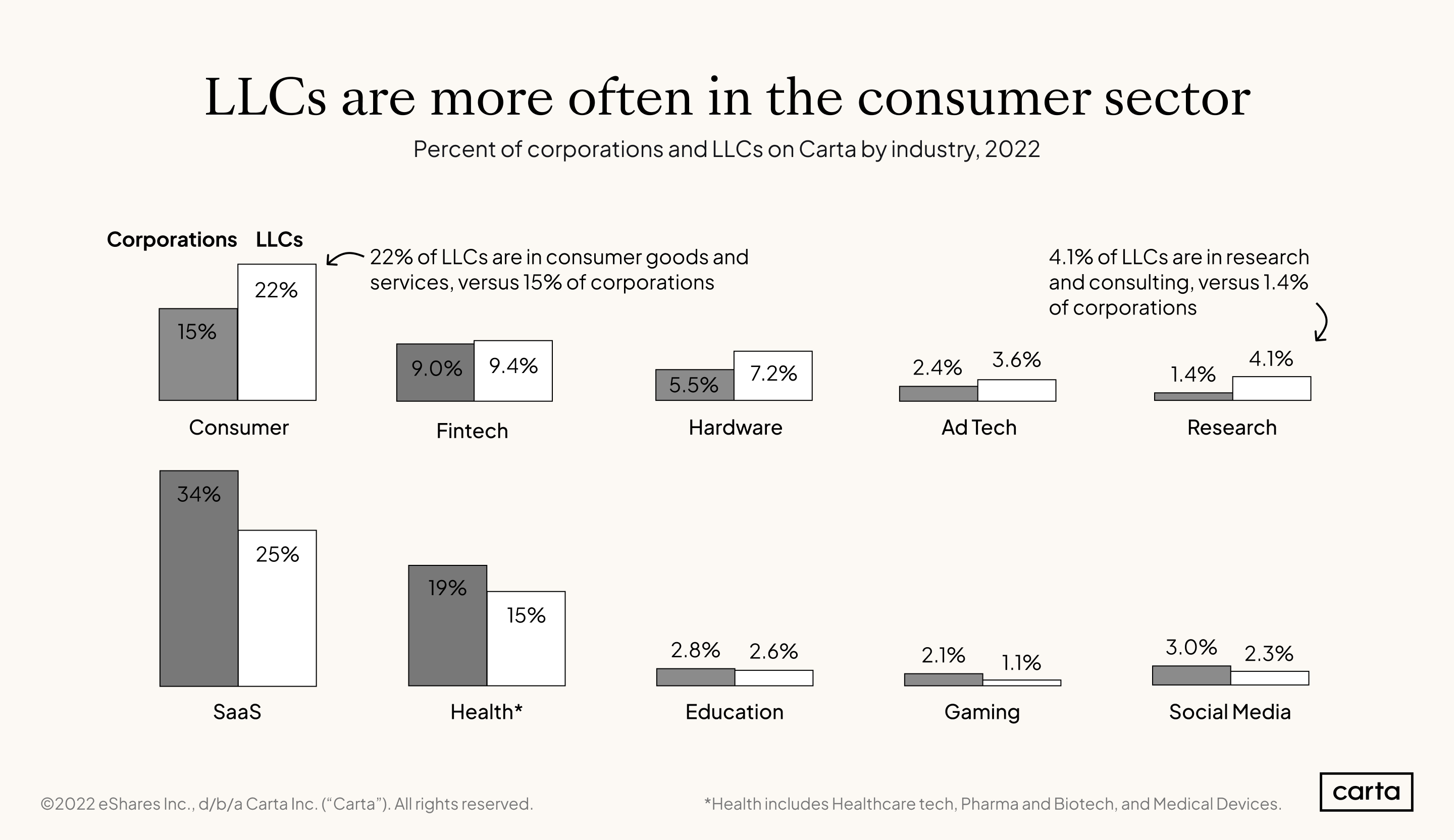

While many LLCs on Carta are tech companies of various kinds, software as a service (SaaS) is relatively less common among this type of company in 2022. Consumer products and services, as well as research and consulting, are more common industries for LLCs than for corporations.

Ownership on Carta

Today, there are two million equity owners on Carta, representing a combined $2.5 trillion in equity value—up from $2 trillion in 2021 and $764 billion in 2020.

Methodology

The Annual Equity Report includes data from more than 1.5 million U.S.-based employee stakeholders who have been issued equity via the Carta platform and over 67,000 founders of corporations who manage their company equity on Carta. Our data on LLCs reflects more than 2,400 LLCs on the Carta platform who use either our core cap table or LLC product.

Sample sizes

We cover analyses only where we have sufficient data. From the point of view of ensuring anonymity, each data point must be backed by at least five entities (people or companies, typically) in order to be included. However, in most cases we have and require much more data than that to reach statistical significance or produce a legible pattern or trend.

Valuing equity

The notional value of an employee’s first equity grant, sometimes shortened to “equity value,” is calculated by multiplying the strike price by the total number of shares in the grant the employee was initially awarded in their role. It is different from the value that the employee may eventually be able to realize from the equity, which is largely driven by opportunities for liquidity and the price an employee is able to get when they sell.

This “equity value” allows us to compare the relative amounts that companies have offered to employees by demographics, geography, or job role and level. Because this number is generated when the equity is first granted, it allows us to compare equity compensation sooner than if we waited for the equity value to mature over time.

Equity granted at earlier company stages tends to have more uncertainty in its future value, which is reflected in lower strike prices in equity grants issued by early-stage companies. The notional value of equity as we are using it does not reflect any variance in the hypothetical possibility of upside between earlier- and later-stage companies (where the growth curve may be steeper the earlier one joins a company, but the attendant risk is likewise different). Nonetheless, we find this metric helpful to compare how companies are choosing to compensate different groups of employees by role, demographics, and location.

To estimate the profit that employees may have realized when exercising their shares, we use the net exercise value, or the difference between the fair market value at the time of exercise and the strike price. We also call this potential profit “paper gain,” as it exists only on paper and may continue to change until the stakeholder is able to access liquidity.

For equity-to-salary comparisons, we compared the value of the first equity grant (which typically vests over four years) in a ratio with the annual salary.

Investor demographics and geography

For our analysis of investor race, ethnicity, and gender, we focused on general partners (GPs) and limited partners (LPs) who are individual natural persons, rather than multiple people or any other entity, such as a trust, retirement account, endowment, LLC, corporation, and so on. The patterns that we found among these people may be different from patterns across the GP and LP ecosystems more broadly.

For geography, we widened our lens to include all GPs and LPs whose mailing addresses (not place of incorporation) are U.S.-based. Therefore, this analysis includes individuals as well as other entities.

Race and ethnicity

Carta offers U.S.-based stakeholders a demographic profile page they can opt to fill out for the purposes of aggregated, anonymized equity compensation analysis. For people who hold multiple stakeholding roles on the Carta platform, their demographic information is attached to each role—such as employee and founder, or GP and LP.

Eight percent of both employees and founders and 12% of limited partners have self-reported their race and ethnicity data to date. Our historical demographic analyses will continue to change as this data becomes more complete each year.“

Hispanic & Latine” is an ethnic category that applies regardless of race; other races include only those who did not self-identify as Hispanic or Latine. We acknowledge that this does not fully represent intersectional identities. We shorten “Black/African-American” to “Black,” and “Hispanic & Latine” to “Latine” for readability—though we know that those terms and the experiences of these groups aren’t identical. The category “East and Southeast Asian” is shortened to “East Asian” throughout the report for readability; this group includes those who the U.S. Census refers to as coming from the “Far East” or “Southeast Asia.” Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders are included in “Other,” alongside people of Indigenous American, Middle Eastern, and mixed backgrounds. As our dataset grows each year, we will look for opportunities to report on each of these groups.

Gender identity

When available, we used a user’s self-reported gender (from their demographic profile) in this analysis. Among employees, we had enough self-reported data for our analysis. For founders and LPs, given the sparseness of the demographic profile dataset (8% of the total), we categorized unknown genders by comparing the stakeholder’s first name to aggregate name data from both the U.S. Social Security Administration and Gender API to yield a more complete dataset. To keep data anonymous, we classified gender using first names only independently of equity data. We considered first names with less than 85% gender accuracy too ambiguous to classify. This may mean that names not popular in the U.S., or that are more often used by both men and women, were excluded more often.

About 1% of those who completed their demographic profile shared that they are nonbinary —meaning that their gender doesn’t fit within the binary of “man” or “woman”; and a smaller percentage elected to self-describe their gender in ways other than man, woman, or nonbinary. In most analyses using gender, there was not a sufficient sample size to report on the experiences of nonbinary people; in these cases, the percentage of men and women are reported excluding nonbinary people and those who self-described their gender in other ways.

LLCs and corporations

This report uses data about corporations that use Carta’s core cap table product, except for the section on limited liability companies (LLCs). Data on LLCs in this report is from customers using Carta’s cap table product, except for the chart showing the growth of LLCs on Carta over time. For this chart, we combined LLCs that are customers of the core cap table product and LLCs that are customers of Carta’s LLC product.

Credits

Editorial: Lian Chang, Kiley Roache, Julie Ross GodarData: Erin Boehmer, Alison Nham, Lucy Wang, and Sanjana Pukalay; with help from Julien Gaillard, Ray Raff, Jessica Ray, Winston Van, and Benno VeenisCommunications: Lauren O’Mahony, Tania Zaparaniuk, Jessica CapibaribeWeb and Design: Jordan Boulter, Samuel Ong Sze Hern, Mike Rojas, Xuefei FiFi ZhangLeadership: Mita Mallick, Jane Alexander, Ryan ChenThank you also to: Addison McLamb, Lara Sherman, Josh Steinfeld, Sara Jane Stephens, Peter Walker, Angela Winegar

Footnotes

1 We’ve chosen to use “Black/African-American” and “Hispanic & Latine” as broad categories, shortened to “Black” and “Latine” for readability—though we know that those groups and their experiences aren’t identical. See the Methodology section at the end of the report for an overview of our data and the decisions we’ve made.

2 The category “East and Southeast Asian” is shortened to “East Asian” in graphs and for the remainder of the text for readability. This group includes those who the U.S. Census refers to as coming from the “Far East” or “Southeast Asia.”

3 In many cases, we found significant differences in data around the employment and equity of people of Asian backgrounds. In charts, we include East Asians and South Asians separately and include the smaller demographics of Pacific Islanders in the “Other” group. See the Methodology section for more information.

4 People are invited to self-report their gender and other demographic information in their profile on the Carta platform. For the first time this year, we have enough employees self-reporting their gender as nonbinary to share some data about their experience. We don’t yet have enough data on nonbinary people for most segments and analyses in this report, and our sample size isn’t large enough for us to say what proportion of employee, founder, or investor populations are nonbinary. But we can say that 1% of those who shared gender information indicated that they are nonbinary. People who don’t fit into the gender binary may be more or less likely to share their demographic information, given stigma or prejudice. See the Methodology section for more information behind the data.

5 RSUs, which do not require exercise, were not included in the analysis of employee exercising.

6 Looking at LPs who are individuals only.

7 Looking at LPs who are individual people.